Cerro

Mulato: El caso de Piedra 274 Cerro

Mulato: El caso de Piedra 274

Maarten van Hoek rockart@home.nl

English version

INTRODUCCIÓN

Estoy

seguro de que todos los respetables investigadores de arte

rupestre están de acuerdo en que el

primer objetivo de la ciencia –y

por consiguiente también de la investigación de arte rupestre– es el de ofrecer información correcta. Esto

significa que todos los datos deben

ser verificables. Esto también significa que los materiales publicados deben estar sujetos

a verificación. Si resulta que en un caso la información publicada es

definitivamente incorrecta, debe hacerse posible emitir una ‘segunda opinión’ que corrija

los errores. Las publicaciones sobre arte rupestre

suelen ofrecer material gráfico, tanto fotografías como transcripciones en blanco y negro, y éstas últimas son a menudo (hasta cierto punto) representaciones subjetivas del diseño actual, razón por las que se considerarán a continuación como objeto

central de revisión y discusión.

El caso de Piedra 274

En este sentido, me gustaría presentar el caso de Piedra 274,

la cual contiene uno de los cerca de 600 petroglifos que

se encuentran en el sitio de arte

rupestre de Cerro Mulato ubicado en el

norte del Perú. Piedra 274 es una roca de tamaño mediano en una posición bastante oculta entre varias grandes piedras en el cuadrante SW de

esta colina y por esta razón

puede ser pasada por alto fácilmente. Su superficie en la parte superior es plana y lisa y posee un único e interesante

diseño (figuras 1 y 2), aunque el ejecutor pudo haber acentuado los bordes de l

a roca con un picoteo superficial (práctica advertida

en otros petroglifos en el Cerro Mulato y Palamenco).

Figura 1. Piedra 274 en el

Cerro Mulato. Fotografía de Maarten van Hoek.

Figura 2. Piedra 274 en el Cerro Mulato. Fotografía de Maarten

van Hoek.

La fotografía digital se ha resaltado y los colores se han retirado para revelar mejor el diseño.

El diseño de Piedra 274 tiene

propiedades muy específicas que

serán discutidas más adelante. Es

importante destacar que el diseño de cualquier petroglifo y sus detalles específicos son decisivos cuando se trata de brindar una interpretación

adecuada a partir de su forma. La transcripción exacta

del diseño también es importante para

aproximarse al contexto espacial y

cronológico. En consecuencia, esto no sólo se aplica al diseño de Piedra 274, sino también a los sitios de arte rupestre,

Cerro Mulato en este caso, y para

la región de los Andes del norte en que se encuentra, lo cual demuestra que es crucial ofrecer una presentación

correcta de cada imagen del arte rupestre.

Con base en lo anterior, y con la presunción de

que los investigadores de arte

rupestre estan de acuerdo en que la

advertencia y transcripción de los detalles de diseño de un petroglifo son esenciales para su correcta interpretación, presento en este artículo dos transcripciones en blanco y negro de Piedra 274 y dejo de

manera imparcial a consideración del lector para juzgar la discrepancia.

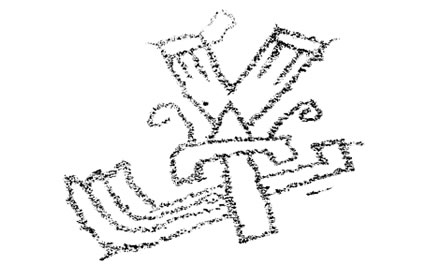

La figura 3 es la transcripción en blanco y negro de Piedra 274 que realicé con base mi

fotografía (figura 1). Se puede

ver en el dibujo (figura

3) y las fotografías (figuras 1 y 2) que el diseño se

compone de finas líneas picoteadas rectas y curvas que a menudo son paralelas. Estas líneas forman probablemente un solo gran diseño, aunque es algo incierto porque es posible que algunas líneas muy débiles continuen a

la izquierda. Estas líneas inciertas han sido omitidas en la figura 3, ya que no distraen de la cuestión planteada en este artículo.

Figura 3. Piedra 274 en el

Cerro Mulato. Dibujo de Maarten van Hoek. Como este dibujo se basa en una fotografía que se ha tomado un poco oblicuamente, el

diseño puede estar un poco distorsionado. Además, el dibujo puede estar incompleto.

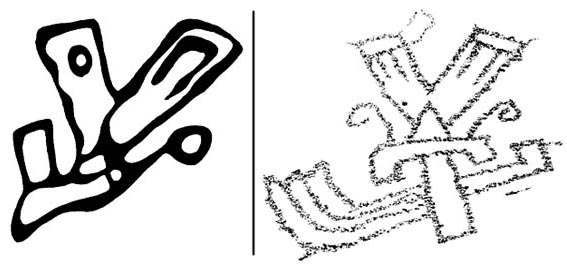

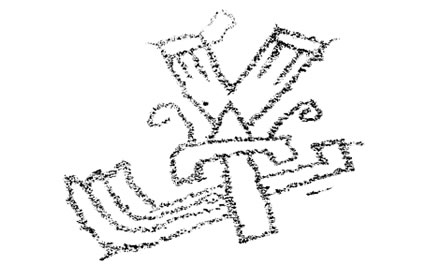

Figura 4. Piedra 274 en el Cerro

Mulato. Dibujo de Núñez Jiménez (1986. Fig. 244).

El único dibujo previo de la Piedra 274 que conozco ha

sido publicado en el libro Los Petroglifos del Perú por Núñez Jiménez (1986: Fig. 244). Este dibujo (figura 4) difiere mucho de la representación en la figura 3. De hecho, he tenido que escanear la fotografía y el dibujo de Núñez Jiménez en varias ocasiones antes de darme

cuenta de que se trata del mismo petroglifo (!). Fue la parte en forma de V del diseño en mi fotografía lo que finalmente me llamó

la atención. Probablemente a causa de este elemento en forma de V (las ‘alas’) Núñez Jiménez tentativamente

sugiere en la leyenda de su dibujo que este petroglifo podría ser un pájaro (¿ave?). Pero el diseño sin duda no es una representación de un ‘pájaro’, a

pesar de que podría simbolizar un ‘pájaro’ (estilizado?), pero esto no puede asegurarse.

¿Por qué es el diseño real de Piedra 274 un

tema tan importante? En primer lugar, la diferencia es demasiado grande para ser científicamente aceptable y el dibujo de Núñez Jiménez ya no puede ser aceptado como fuente de información correcta. En segundo

lugar, el diseño de la Figura 3 demuestra claramente que el petroglifo es un ejemplo de la iconografía del Período Formativo del norte de los Andes (la zona entre la ciudad de Arequipa en

Perú hasta la frontera con Ecuador). Este específico estilo de arte rupestre lo he catalogado como el estilo MSC,

porque refuto la idea de que diseños ‘Chavinoides’ hayan sido fabricados por la cultura Chavín (para

más detalles ver Van Hoek 2011a). Por el

contrario, sostengo que la cultura Cupisnique puede haber sido la responsable de tales diseños. Esta importante

conclusión nunca se podría haber hecho si sólo se tomara como referencia el dibujo de Núñzez Jiménez.

En esta conclusión es decisiva la estructura de 'bandas' (modular width) de varias partes del diseño, el elemento en forma de U-invertida y el

triángulo central unido. La forma

de U-invertida también se encuentra de forma inequívoca

en el estilo MSC de petroglifos y pinturas rupestres de Cerro Mulato (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig. 75), Río Seco de Santa Ana (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig. 64) y en el Alto de la Guitarra (Van Hoek 2011a:

Figs 53, 60 y 76). Incluso los conocidos antropomorfos en Palamenco (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig.

31) muestra las formas de U-invertida. El

triángulo se produce en varias otros petroglifos y pinturas rupestres en estilo MSC (Van Hoek 2011a: Figs 39, 43, 44, 99 y 122). El elemento en forma de V tiene alguna semejanza con el arnés en el petroglifo antropomorfa en el Alto de la Guitarra (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig. 40). La

‘cola’ del diseño remite a la ‘cola’ del biomorfo en Piedra CM-335 en el Cerro Mulato (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig. 42).

CONCLUSIÓN

Se demuestra ahora que el dibujo incorrecto publicado por Núñez Jiménez inhibe la correcta interpretación y contextualización del diseño de Piedra 274. En este sentido, lamento decir que muchos

dibujos por Núñez Jiménez son inexactos o

incorrectos, tal como en el caso de Piedra 274. En mi reciente libro Petroglifos del Perú. Siguiendo

los pasos de Antonio Núñez Jiménez (2011b) he consignado más de 500 casos. El caso de la Piedra 274 no se menciona en este libro al igual que varios otros casos en el Cerro Mulato. Por

lo tanto, probablemente el 20% de la información gráfica que se ofrecen en el libro de Núñez Jiménez es inexacta o

incorrecta. En mi última

publicación (2011b) he

incluido numerosas ilustraciones para

probar mi caso.

No encuentro ningún problema en absoluto con cualquier investigador del arte rupestre que produce un dibujo incorrecto de una imagen de arte rupestre, sobre todo cuando este ‘defecto’ se explica por factores ajenos al

control del investigador. Especialmente las condiciones de iluminación en el

momento de la registro y/o los

métodos de registro son a menudo 'la culpa' de dibujos inexactos o

incorrectos. Estas cosas pasan. El

investigador de arte rupestre no es el culpable de esto pues sucede accidentalmente.

Sin embargo, encuentro un problema cuando se publica el mismo diseño por otro investigador de arte rupestre –quien pueden demostrar que los dibujos publicados anteriormente son

definitivamente incorrectos– ignorándolo o incluso tergiversándolo. En el mundo científico debe ser posible cuestionar una publicación cuando hay disponible evidencia sólida.

Todos los investigadores de arte rupestre ahora debe saber que mucha

de la información en el libro de Núñez Jiménez es incorrecta o al menos, cuestionable (a pesar de

las muchas interpretaciones correctas). Sólo cuando alguien ha visto un petroglifo en el campo, será capaz de ver las

diferencias a menudo inaceptables entre los dibujos de Núñez Jiménez y los

diseños reales. Sin embargo, varios investigadores de arte rupestre han copiado –no

malintencionadamente, pero si sin cuestionamientos– transcripciones incorrectas o inexactas realizadas por Núñez Jiménez en sus

propias publicaciones (Hostnig 2003, Pozzi-Escot 2009) y algunos de estos investigadores basan

sus ‘comentarios’ (Bednarik 2011) u 'observaciones’ (Guffroy 1999) sobre los dibujos incorrectos sin haber visto los petroglifos en el campo. Como consecuencia de ello también sus ‘comentarios’ y ‘observaciones’ serán por lo menos cuestionables o incorrectos.

Las observaciones en mi libro (2011b) no pretenden de ninguna manera ser un ataque a la

persona de Antonio Núñez Jiménez. El principal objetivo de mi libro no es específicamente criticar la forma en que los diseños han sido representados en su obra. El único objetivo es exponer el impacto negativo que sus transcripciones han tenido en los investigadores de arte rupestre en el pasado (véase, por ejemplo Van Hoek 2011b: 45) y para advertir el efecto negativo que tendrá en el futuro, si no se hace algo al respecto. La única

manera de hacerlo es analizar y

publicar los hechos. Esto es lo que he intentado hacer, tanto en mi

último libro como en este trabajo.

Nadie debe dudar de mi admiración por el trabajo en el campo y la

investigación posterior realizada por Antonio Núñez Jiménez. Su

trabajo y dedicación de hecho son

asombrosos. Su libro sigue siendo

un ‘must have’. Sin embargo, los investigadores de arte rupestre deben ser plenamente conscientes de los riesgos cuando se utilizan, sin

crítica, copias del material ilustrativo de la obra de Núñez Jiménez. Intentaré seguir advirtiendo sobre cualquier investigador de arte rupestre que de manera acrítica utilice dibujos inexactos realizados por Antonio Núñez Jiménez. Una

de las líneas de mi libro (2011b) dice 'no matar al mensajero’. Espero que esta solicitud sea respetada. Ser imparcial es una de

las características de un científico sincero.

—¿Preguntas,

comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

Cómo

citar este artículo:

van Hoek, Maarten. Cerro

Mulato: el caso de Piedra 274.

En Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/cerromulato.html

2012

bibliografía

Bednarik, R. G. 2010. In: Troncoso, A. & D. Jackson. 2010. Images that travel: ‘Aguada’ rock art in

north-central Chile. Rock Art Research. Vol. 27, Number 1. pp 43 - 60. Melbourne, Australia. With RAR Comments by Natalia Carden, Dánae Fiore and Robert G. Bednarik;

with RAR Reply by the authors.

Guffroy,

J. 1999. El Arte Rupestre del antiguo Perú. Edit. IFEA / IRD. Lima, Perú.

Hostnig, R. 2003. Arte

rupestre del Perú. Inventario Nacional. CONCYTEC, Lima, Perú.

NÚÑez

JimEnez, A. 1986. Petroglifos del Perú. Panorama mundial del

arte rupestre. 2da. Ed. PNUD-UNESCO - Proyecto Regional de Patrimonio

Cultural y Desarrollo, La Habana.

Pozzi-Escot,

M. 2009. Los Petroglifos de Toro Muerto (Valle de Majes,

Arequipa-Peru). Inventario y Registro. In: Crónicas sobre la Piedra: Arte Rupestre en las Américas. Eds: Marcela Sepúlveda, Luis Briones and Juan Chacama. VII Simposio Internacional de Arte Rupestre - Arica,

2006. Capitulo 4, pp 349 - 361. Arica, Chile.

Van Hoek, M. 2011a. The Chavín Controversy - Rock Art from the Andean Formative period.

Privately Published using the BLURB Creative Publishing Service. Oisterwijk,

The Netherlands. http://www.blurb.com/bookstore/detail/1943422.

VAN

HOEK, M. 2011b. Petroglyphs

of Peru - Following the Footsteps of Antonio Núñez Jiménez. Privately Published using the BLURB

Creative Publishing Service. Oisterwijk, The Netherlands. http://www.blurb.com/user/store/desertandes.

English version

Cerro Mulato: The Case of Piedra 274

Maarten van Hoek rockart@home.nl

INTRODUCTION

I am sure that every respectable rock art

researcher will agree that the first goal of science -and also of rock art

research - is to offer correct information. This means that all data must be verifiable. This also means that

published material should be subject to verification. If it now proves that

published information is definitely incorrect, it must be possible to allow for

a ‘second opinion’ which fixes the errors. It should even be appreciated if

incorrect information is corrected in a publication, and it should not matter

who made the errors and who offers those corrections. Rock art publications

often offer graphical material, both photographs and black-and-white

illustrations, and especially the latter are often (to a certain degree)

subjective renderings of the actual design. Therefore I focus on

black-and-white illustrations in this article.

the case of Piedra 274

In this respect I would like to present the

interested reader the case of Piedra 274. This stone is one of the perhaps more than 600 petroglyph boulders that

are found at the extensive rock art site of Cerro Mulato in the north of Peru. Piedra 274 is a medium sized boulder in

a rather concealed position amongst several large boulders in the SW quadrant

of this low hill and may easily be overlooked for that reason. Its upward

facing flat and smooth surface bears a most interesting design (Figures 1 and

2); the only petroglyph on this boulder (although the manufacturer of the

design might have accentuated the edges

of the boulder with superficial pecking - a practice reported at other

petroglyph boulders at Cerro Mulato and Palamenco).

Figure 1. Piedra 274 at Cerro Mulato. Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 2. Piedra 274 at Cerro Mulato. Photograph by Maarten van Hoek. The photograph has been digitally enhanced by

me and the colours have been removed to better reveal the design.

The design on Piedra 274 has very specific properties that will be discussed

further on. Importantly, the layout of any design and its specific details are

decisive when it comes to an appropriate interpretation of the design itself.

The exact layout is also important to access the spatial and chronological

context of the design. Consequently this not only applies to the design on Piedra 274, but also to the rock art

site itself - in this case Cerro Mulato - and the region - the northern Andes -

it is found in. It proves that offering a correct rendering of every rock art

image is crucial.

Having said this, I continue to say that I am

also sure that every respectable rock art researcher will agree that details of a rock art design are

essential in a correct scientific rendering and acceptable interpretation of

every rock art image. In this respect I offer the interested reader two black-and-white

renderings of Piedra 274 and I leave

it to the hopefully unbiased reader to judge the discrepancy.

Figure 3 is the black and white drawing that I

made (at home) of Piedra 274. The

drawing is based on the photograph (Figure 1) that I made of Piedra 274. You can see in the drawing (Figure

3) and the photographs (Figures 1 and 2) that the design consists of finely

pecked (straight and curved) lines that often run parallel to each other. Those

lines probably form one large design, although it is uncertain if the drawing

that I made offers the complete design, as very faint lines possibly continue

to the left. These uncertain lines have been omitted in Figure 3 as they do not

distract from the issue raised in this article.

Figure 3. Piedra 274 at Cerro Mulato. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek. As this drawing is based on a photograph that has

been taken slightly obliquely, the design may be somewhat distorted. Also, the

drawing may be incomplete.

Figure 4. Piedra 274 at Cerro Mulato. Drawing by Núñez Jiménez (1986. Fig. 244).

The only other drawing of Piedra 274 that I know of has been published in the book about the

petroglyphs of Peru by Núñez Jiménez (1986: Fig. 244). The drawing by Núñez

Jiménez (Figure 4) differs very much from the rendering in Figure 3. In fact, I

had to scan the photograph and the drawing(s) by Núñez Jiménez several times

before I realised that it concerned the same petroglyph! It was the V-shaped

part of the design that finally drew my attention to my photograph. Probably

because of this V-shaped element (the ‘wings’) Núñez Jiménez tentatively suggested in the caption to his drawing

that this petroglyph might be a bird

(¿ave?).

But the design definitely is not a representation of a ‘bird’, although it might symbolise a (stylized?) ‘bird’; but this we will never be sure of.

Why is the actual design of Piedra 274 such an important issue? First of all, the difference is too big to be scientifically

acceptable and the drawing by Núñez Jiménez can no longer be accepted as

offering the correct information. Secondly, the design in Figure 3 clearly

demonstrates that the petroglyph is an example of the iconography of the

Formative Period of the northern Andes (the area from the town of Arequipa in

Peru to the border of Ecuador). This specific rock art style has been labelled

the MSC-style by me because I refute the idea that ‘Chavín-looking’ designs

have been manufactured by the alleged Chavín culture (for full details see Van

Hoek 2011a). On the contrary, I argue that the Cupisnique culture(s) has (have)

been responsible for such designs. This important conclusion could never have

been made if only the drawing by Núñez Jiménez would have been available.

Decisive in this conclusion are the ‘banded’

structure (modular with) of several parts of the design; the elongated U-shaped

element and the attached and centrally placed triangle. The elongated U-shaped

element is also found in unequivocal MSC-style petroglyphs and rock paintings

at Cerro Mulato (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig. 75), Río Seco de Santa Ana (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig. 64) and at Alto de la Guitarra (Van Hoek

2011a: Figs 53, 60 and 76). Even the well known anthropomorph at Palamenco (Van

Hoek 2011a: Fig. 31) shows those elongated U-shaped elements. The triangle

occurs at several other MSC-style petroglyphs and rock paintings (Van Hoek

2011a: Figs 39, 43, 44, 99 and 122). The V-shape element has some resemblance

with the headgear in the anthropomorphic petroglyph at Alto de la Guitarra (Van

Hoek 2011a: Fig. 40). The feather-like ‘tail’ of the design reminded me of the

tail of the biomorph on Boulder CM-335 at Cerro Mulato (Van Hoek 2011a: Fig.

42).

conclusion

It now proves that the incorrect drawing

published by Núñez Jiménez inhibits the correct interpretation and

contextualisation of the design on Piedra 274. In this respect I regret to say that many drawings by Núñez Jiménez are

inaccurate or incorrect in the same way as is the case with Piedra 274. In my recent book ‘Petroglyphs of Peru. Following the footsteps

of Antonio Núñez Jiménez’ (2011b) I have accumulated more than 500 such

cases. The case of Piedra 274 is not

mentioned in the book as are several other instances at Cerro Mulato.

Therefore, probably 20% of the graphical information offered in the book by

Núñez Jiménez is inaccurate or incorrect. In my latest publication (2011b) I

have included numerous illustrations to prove my point.

I have no

problem at all with any rock art researcher who produces an incorrect

drawing of a rock art image, especially when this ‘flaw’ is explained by factors

beyond the control of the researcher. Especially the lighting conditions at the

moment of recording and/or the recording methods are often ‘to blame’ for

inaccurate or incorrect drawings. These things happen. The rock art researcher

is not to blame for this as this happens unintentionally.

However, I do have a problem when the

publication of the same design by another rock art researcher - who can prove that previously published drawings

are definitely incorrect - is ignored or even boycotted. In the scientific

world it must be possible to criticise (part of) a publication when solid

evidence is available.

Every rock

art researcher should now know that much of the information in the book by

Núñez Jiménez is incorrect or at least questionable (despite the very many

correct renderings). Only when someone has seen a petroglyph in the field, he

or she will be able to see the often unacceptable discrepancies between the

drawings by Núñez Jiménez and the factual designs. Yet several rock art

researchers have copied - unintentionally but also uncritically - incorrect or

inaccurate illustrations made by Núñez Jiménez in their own publications

(Hostnig 2003; Pozzi-Escot 2009) and some of those researchers base their ‘comments’ (Bednarik 2011) or ‘observations’ (Guffroy 1999) on those

incorrect drawings without having seen the actual petroglyphs in the field. As

a consequence also those ‘comments’ and ‘observations’ will therefore be at

least questionable or even incorrect.

The observations in my book (2011b) are not in any way meant as an attack

on the person of Antonio

Núñez Jiménez (regrettably, this has been suggested by a few obstructive

persons who once claimed to be friends and colleagues). The main objective of

my book is not specifically

criticizing the way the illustrations have been represented in the Núñez

Jiménez book. The only goal is to expose the negative impact that his illustrations have had on rock art researchers

in the past (see for instance Van Hoek 2011b: 45) and to warn for the negative effect it will have in

the future, if nothing happens. The only way to do this is to analyze and publish

the facts. This is what I have done, both in my latest book and in this paper.

No-one should

doubt my admiration for the fieldwork and subsequent research by Antonio Núñez

Jiménez. His fieldwork and dedication indeed have been amazing. His book is

still a ‘must have’. However, every

modern rock art researcher must be fully aware of the risks when he or she

uncritically uses (copies) illustrative material from the Núñez Jiménez book.

Actually, I will criticize any rock art researcher who will uncritically use whichever drawing made by

Antonio Núñez Jiménez without mentioning those risks, especially after my

comments have been published via my book (2011b). One of the lines in my book

(2011b) reads ‘do not shoot the

messenger’. I hope this request will be respected. Being unbiased is one of

the characteristics of a sincere scientist.

—¿Preguntas,

comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

Cómo

citar este artículo:

van Hoek, Maarten. Cerro

Mulato: the case of Piedra 274.

Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/cerromulato.html

2012

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bednarik, R. G. 2010. In: Troncoso, A. & D. Jackson. 2010. Images that travel: ‘Aguada’ rock art in

north-central Chile. Rock Art Research. Vol. 27, Number 1. pp 43 - 60. Melbourne, Australia. With RAR Comments by Natalia Carden, Dánae Fiore and Robert G. Bednarik;

with RAR Reply by the authors.

Guffroy,

J. 1999. El Arte Rupestre del antiguo Perú. Edit. IFEA / IRD. Lima, Perú.

Hostnig, R. 2003. Arte

rupestre del Perú. Inventario Nacional. CONCYTEC, Lima, Perú.

NÚÑez

JimEnez, A. 1986. Petroglifos del Perú. Panorama mundial del

arte rupestre. 2da. Ed. PNUD-UNESCO - Proyecto Regional de Patrimonio

Cultural y Desarrollo, La Habana.

Pozzi-Escot,

M. 2009. Los Petroglifos de Toro Muerto (Valle de Majes,

Arequipa-Peru). Inventario y Registro. In: Crónicas sobre la Piedra: Arte Rupestre en las Américas. Eds: Marcela Sepúlveda, Luis Briones and Juan Chacama. VII Simposio Internacional de Arte Rupestre - Arica,

2006. Capitulo 4, pp 349 - 361. Arica, Chile.

Van Hoek, M. 2011a. The Chavín Controversy - Rock Art from the Andean Formative period.

Privately Published using the BLURB Creative Publishing Service. Oisterwijk,

The Netherlands. http://www.blurb.com/bookstore/detail/1943422.

VAN

HOEK, M. 2011b. Petroglyphs

of Peru - Following the Footsteps of Antonio Núñez Jiménez. Privately Published using the BLURB

Creative Publishing Service. Oisterwijk, The Netherlands. http://www.blurb.com/user/store/desertandes.

[Rupestreweb Inicio] [Introducción] [Artículos]

[Noticias] [Mapa] [Investigadores] [Publique] |

![]()