An analisis of the evaluation and diagnostics to environmental impacts in rock art stations of Guaniguanico Montain Range, Cuba

Racso Fernández Ortega racsof@sangeronimo.ohc.cu

Dany Morales Valdés

Dialvys Rodríguez Hernández

Victorio Cué Villate

Hilario Carmenate Rodríguez

Cuban Group of Rock Art Researches (GCIAR)

Cuban Institute of Anthropology (ICAN)

Artículo publicado originalmente en Memorias de la Conferencia Internacional de Arte Rupestre 2012, por el 25 aniversario de Indira Gandhi, National Center for the Arts, Nueva Delhí, India.

RESUMEN

En los marcos del proyecto de evaluación y diagnóstico del patrimonio arqueológico y sociocultural de Cuba, desarrollado por un colectivo del Departamento de Arqueología del Instituto Cubano de Antropología (ICAN), se efectuó una expedición de conjunto con miembros del Grupo Cubano de Investigaciones del Arte Rupestre (GCIAR) para evaluar los impactos medioambientales que están deteriorando al dibujo rupestre de esta provincia. En este sentido de manera aleatoria de las 37 estaciones que posee la región se seleccionaron 17, lo que representa el 45,9%), para conocer el estado de conservación de las mismas, mediante la aplicación del método de evaluación y diagnóstico del patrimonio arqueológico que aplica nuestra institución. La referida metodología permite clasificar las acciones en naturales y antrópicas para la mejor búsqueda de soluciones que permitan eliminarlas o la ejecución de acciones paliativas para frenar, en alguna medida, su deterioro. Para ello en el trabajo se definen, enumeran y caracterizan las acciones y los impactos que más perjudican el estado de conservación de este importante patrimonio.

Palabras claves: Evaluación,

diagnóstico, impacto medioambiental, dibujo rupestre, Cuba.

ABSTRACT

In the marks of the research project “Evaluation and diagnosis of the archaeological and sociocultural heritage of Cuba”, developed by a group of the Department of Archaeology of the Cuban Institute of Anthropology (ICAN), an expedition was made joined to members of the Cuban Group of Rock Art Researches (GCIAR) to evaluate the environmental impacts that are affecting the rock drawings of Pinar del Río province. 15 stations of 38 located in that area were randomly selected to apply the evaluation and diagnosis methodology of environmental impacts that is used by ICAN. The applied method allows classifying the natural and anthropic actions for the best search of solutions to eliminate the damage, or the practice of palliative actions to stop, in some way, its deterioration. So, the actions and impacts that affect in a deeper way the state of conservation of this Cuban important heritage are defined, enumerated and characterized in this paper.

Keywords: Evaluation, diagnosis, environmental impact, Rock Art, Cuba.

INTRODUCCIÓN

The problem of

the protection and conservation of rock art is a concern to universal scale,

linked to the real fact that annually a great number of stations get lost

because of diverse factors, but mainly for the uncontrollable and negative

actions of humans. Three examples in our country are the rock art stations of

Cueva Mesa and Cueva La Jarra in the municipalities of Viñales, Pinar del Río,

and San Cristóbal, in Artemisa Province, respectively, or the Cueva de los

Golondrinos in Baracoa, Guantánamo Province. These stations were victims of

mechanisms of adaptation because of their "setting in value" or

habilitation of its archaeological places with different purposes and

strategies, without a true impact study that analysed the consequences of those

activities on their paintings. The harmful results on the rock art began to

occur and as a consequence they are getting deteriorated sooner than if the

natural processes occurred.

As it is very well-known, the pictographs and petroglyphs are products

of the social conscience, and they regrettably remain joined to the natural

aging of their supports, pigments and agglutinants, becoming themselves along

time in a truly vulnerable and fragile resource.

Even so, this ancient heritage has remained for us –even, in many

occasions, with an antiquity of several thousands of years–, what shows

evidence of its good invoice, resistance and adaptation to the environmental

changes that have taken place from its creation. That is the reason why in some

occasions the opinion emitted by some officials, that regrettably "the

development" cannot depend on to a manifestation that sooner or later will

disappear, it is not well considerate and accepted (1).

1. Nowadays, a non-sustainable development that doesn't take advantage of

the particularities of the surrounding ecosystem of each selected area, is unthinkable.

The value of the historical-cultural heritage represents an important source of

power to the national identity and the residents could be transformed into main

actors for its protection and conservation.

|

However, the Cuban experience demonstrates that the anthropic

affectation, either voluntary or not, is the biggest source of irreversible

aggressions suffered by this manifestation (Fernández and González 2001). This

bases the urgent necessity to protect the Cuban rock art registrations with

effectiveness, in their environmental context, what is at least, tried to be

analysed in this work related with the rock art stations of Guaniguanico Mountain

Range, in the western side of Cuba.

With this objective, in the Cuban Institute of Anthropology (ICAN),

during the years 2006 to 2008, the research project PNAP/0409 "Evaluation

and Diagnosis of the Archaeological and Sociocultural Patrimony of Cuba"

was developed by a team of the Department of Archaeology, due to the quick

process of economic and social development occurred during the last decades,

that has caused the affectation and/or threat to a sensitive number of

archaeological places along the country.

Because of that, in June of 2007 and with

members of the Cuban Group of Rock Art Researches, it was determined to carry

out a study based on the approach accepted by the international experience,

that the bad anthropic manipulation of the ecosystems settled around rock art

stations, is the fundamental cause that provokes secondary effects such as, the

presence of microorganisms, of plants and opportunists zoological species that

damage this millennial irreversible heritage.

THE AREA OBJECT OF STUDY

In the western side of the Cuban island, two mountainous elevations are

located, extended along an important area of Pinar del Río and Artemisa

Provinces. This geographical accident is a mountain range well-known with the

aboriginal name of Guaniguanico; it is projected almost parallel to both north

and south costs, and it has several physical-geographical divisions differed to

each other by its peculiar natural characteristics. The superficial extension

of Guaniguanico Mountain Range is around 3 102 km2 and it spreads from West to

East for about 150 kms approximately from the Cerros de Guane until the

elevations located in Cayajabos, in the central part of the current Artemisa.

In the north and south sectors, surrounding the mountain range, the Llanura Ondulada and the Llanura Deltaica are located,

-extended around 10 and 20 km of the coast, and expanded until 20 and 30 km of

the sea, respectively.

The mountain range “Sierra de los Órganos” is located in the western

part of Guaniguanico, and is very old in geological terms. It exhibits a

characteristic flora well-known as Vegetation Complex of Mogotes growing on the

typical carsic “mogotes”, among which there are fertile valleys with floors of

high quality.

In the East area of Guaniguanico, the “Sierra

del Rosario” is located, the youngest section in this orographic system with

altitudes over the 500 msnm., and with a vegetation of evergreen forest. The

“Pan de Guajaibón” –named with another aboriginal term– is located

among both mountains ranges, and it is the highest elevation of western Cuba,

with 700 msnm., and similar vegetation of that of Sierra del Rosario.

The Guaniguanico mountain range, mainly constituted by calcareous rocks,

concentrates some of the biggest cave systems of the country, with smaller

caves and rock shelters systems in. The ancient communities, first residents of

the territory, were attracted by the exploitation of the fauna and vegetation

of these elevations that guaranteed the development of the survival activities

of them. They used these caves taking advantage of them as establishment towns,

funeral and nature magic-nun sites. These underground places have important water

resources that also slip as streams of small and middle flow, favouring to the

habitability conditions of the aboriginal residents. That is why it is common

to find in the caverns of this wide orographic system, outstanding

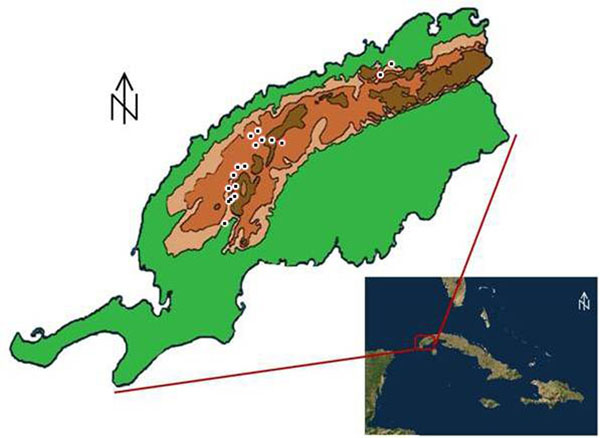

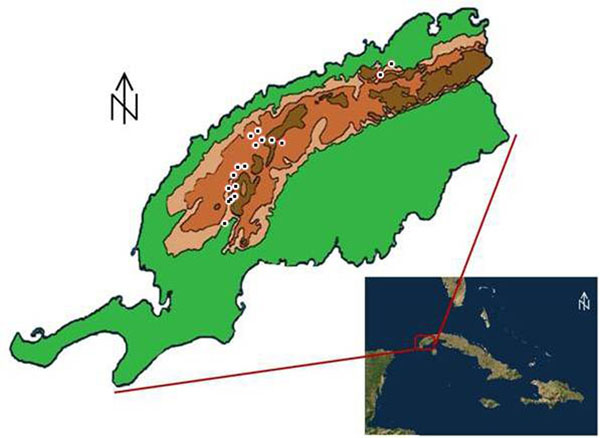

archaeological and rock art evidences (Chart I, figures 1).

No.

|

MUNICIPALITY

|

KIND OF STATION

|

TOTAL

|

PICTOGRAPHIC

|

PETROGLIPHIC

|

MIXED

|

1

|

Guane

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

2

|

2

|

Minas de Matahambre

|

10

|

1

|

-

|

11

|

3

|

Viñales

|

5

|

2

|

2

|

9

|

4

|

La Palma

|

6

|

-

|

-

|

6

|

5

|

Pinar del Río

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

6

|

Candelaria

|

-

|

1

|

-

|

1

|

7

|

Bahía Honda

|

3

|

-

|

-

|

3

|

8

|

San Cristóbal

|

1

|

3

|

-

|

4

|

TOTAL

|

28

|

7

|

2

|

37

|

|

| Chart I.- Composition of the

rock art stations for municipalities in Guaniguanico Mountain Range.

|

|

| Fig. 1.- Cartographic location

of the rock art stations evaluated in Guaniguanico Mountain Range, Cuba.

|

Crono-cultural

Relationship

The territory referred throughout this communication was evidently

inhabited in most parts by aboriginal people belonging to fisher-gathering

communities (Alonso, 1995 and Moreira, 1999), which were extended throughout

the Cuban island, and, deduced by the evidences of the archaeological

registration, they occupied practically the whole geographical space of the

current provinces of Pinar del Río and Artemisa.

The prints of the passing of farming groups for this area, are so far

quite dispersed and reduced, what seems to indicate that theirs arriving to this

area was still in the exploration and recognition phase, and not in the

conquest and occupation stage. This has been able to be interpreted by the

study of the archaeological pieces recovered in places and caves of the provinces

Pinar del Río, Artemisa, Havana and Mayabeque; or by the pictographs registered

and documented in caves such as Pluma, García Robiou and Solapa de la

Perdiguera, in the provinces of Matanzas, Mayabeque and Pinar del Río,

respectively. On the other hand, the permanent and stable establishments of

agricultural aboriginal populations in the west region of Cuba, took place

after the collision with the Europeans, as well as can be interpreted through rock

art manifestations like "the bovine" found in the cave system Guara,

in Mayabeque territory, or as can be demonstrated it the transculturation´s

ceramic sample in Guanabacoa, where the Europeans forced an aboriginal

establishment.

Because of what has been previously expressed, we should consider that

the fisher-gathering-hunting communities were very probably those that executed

the generality of the well-known rock art manifestations in the region,

accepting that the inherited registrations of these groups seem to be

characterized by a tendency toward abstract forms and simple geometric

representations, standing out the concentric circles.

It is also characteristic of these human collectives a style of chaotic

lines, without order neither reason, as if the artist follows with the

instrument the sinuosities that the selected support capriciously imposed, and

where the stains are also common (Fernández et.

al. 2009b), it also has been possible to appreciate that they used red and

black colours like the more frequent ones (Moreira, 1999 and Fernández et. al. 2009b). Many of these elements

are common in the studied stations, as well as the use of red and black

pigments, which were used in 88% of the total of the analyzed places.

Authors like Rosa (1996), Alonso et.

al. (2002) and González (2008) outlined that several stations can be

associated with the drawing art of African origin, linked to the graphic

expressions of the fugitive slaves of the coffee and sugar plantations that

were abundant in the area between XVI to XIX centuries.

The radio-carbonic dates available for this territory were unfortunately

not carried out directly on the rock art, but in the archaeological

registrations rescued in archaeological locations, so they are associated to

the base material found in the rock art stations.

In this sense, we should assume that the manifestations were carried out

by fisher-gathering-hunting aboriginal communities, in one period between 3320

a.n.e. as earlier limit and 1200 d.n.e, as the late one, considering that the

earlier dated one belongs to Cueva de la Lechuza in San Cristóbal municipality,

with 5270 + 120 AP, and the latest to Mogote de la Cueva in Pinar del Río municipality

with 650 + 200 AP (Pine, 1995: 2 and 5). However, the authors consider that

this proposal should be taken just to orientate the research, first, because

the experience has demonstrated that it is not always opportune to link the

archaeological registration located in the rock art station, directly with the

drawings, and second, due to the fact that there aren't enough quantity of

absolute dates to carry out a good association between both elements.

It can be also deduced that for the few stations that are considered as

the fruit of the ideological and cultural activity of the communities

well-known as Farmers, Agroalfareros or Islander Taino, one of the authors

(Fernández, 2012) has achieved the identification of numerous designs

characteristic of their iconography and even some ideographic representations

that remember to the deities of the mythological vault of these groups common

to Cuba and other Antilles islands. That allows assuming as executioners of

these graphic registrations to members of the Arawak linguistic branch with a

producer economy and a social gentile organization (Tabío and King, 1966: 202;

Guarch, 1978:108), Agroalfarero (Dacal and Rivero de la Calle; 1986: 140;

Tabío, 1991: 23), nowadays denominated Farmers (Moreira, L., 1999: 149). In

their unavoidable advance toward the occident of the national territory, they

already began the marks that defined the new landscapes that constituted

unequivocal samples of the passing by of a socially different group for the

territory, to settle down and with other patterns to the selection of the

sacred spaces.

In accordance with the radio-carbonic dates of the farming places

obtained to Cuba, it can be determined that this stage was developed among 820

DNE (1120 + 160 to. AP), according to the older dated one obtained in Residuario

del Paraiso in Santiago de Cuba (Pino, 1995: 10) and 1785 DNE (165 + 60 to.

AP), obtained for Aguas Gordas in the eastern Holguín province (Pino, 1995:

11).

THE ENVIRONMENTAL AFFECTATIONS

TO THE ROCK ART HERITAGE

The threats to the rock art were explained in extensive in the article

"The conservation of the Cuban rock art patrimony. Current situation and

perspectives" that was published in Boletín del Gabinete de Arqueología

(Gutiérrez, Fernández and González 2007). In this occasion, and seeking to be

more precise, a specific area of the Cuban territory has been selected to deepen

in the study of its deterioration and the threats that this archaeological

region faces.

The particular

study of the environmental affectations to the graphic patrimony demanded to

divide the threats that it faces in four groups, to facilitate the better

analysis of the damages. The classification had the origin of the damages as a premise,

and they were differentiated in Natural, Industrial, Anthropic and Cultural;

those that are integrated by other groups, in dependence of the type of

affectation.

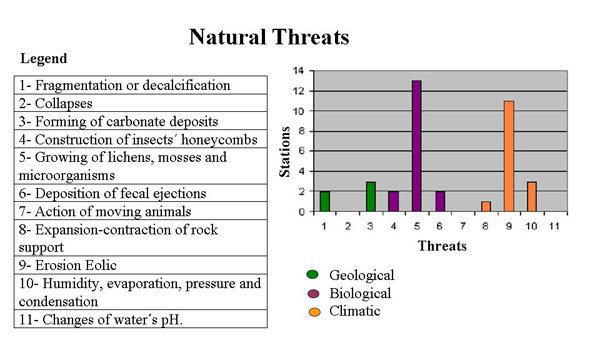

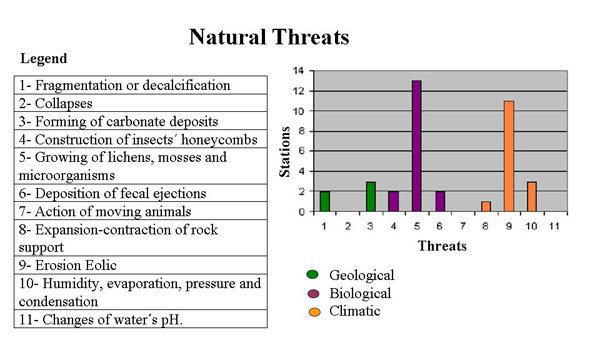

Natural Threats

The

threats denominated natural are those

that appear as a result of the planetary typical processes of nature, in which

the man doesn't have a primary or direct participation, such as the geological,

carsological, biological or climatic alterations. Since the point of view of

their categorization they can be subdivided in the following categories or

types:

Geologic: In this group are included the damages taken place by

the formation of deposits of carbonates on the areas with graphic

representations; also those detachments or collapses of blocks or fragments of

rocks as a result of the structural adjustment of the localities. The cracking

or scaling is also included; it happens when there is cracking or jump of small

parts of the support that contains the graph, because of the same causes that

the fragmentation occurs.

Biological: Here are included the

damages caused by the natural growth of mushrooms, lichens, mosses, algae,

ferns and other vegetable organisms, on the supports in which the graphs were

carried out. Another common phenomenon is the faecal ejections of bats,

rodents, birds and other permanent or eventual inhabitants of the stations; as

well as the action taken place by some animals when moving on graphs, or the

construction of honeycombs and nests by insects and birds.

Climatic: In this kind of

threat are included the eolic erosion, the changes of humidity –relative

and absolute– in the caves environments, as well as the evaporation,

condensation, pressure of CO2, oxidation, and other microclimatic variables.

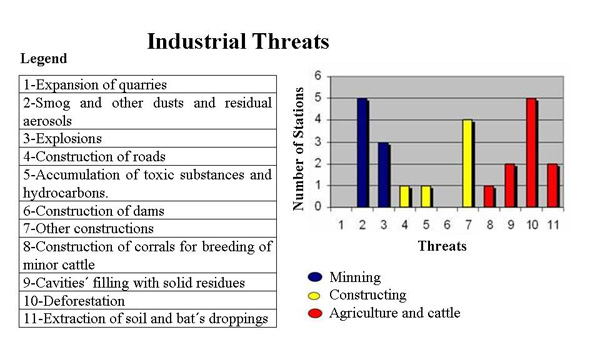

Industrial Threats

Those denominated industrial

threats, are all the actions provoked by modern man as secondary effect by

modifying the environment and the ecosystem that surrounds the stations, with the

purpose of increasing the economic and industrial development.

It has been observed that in occasions, when there is a reference to the

environment of the rock art stations, it is common to think in the space

surrounding it, however meticulous field studies have demonstrated, for example,

that the effects of the emanations of hidrosulfhuric gas of petroleum wells in

the north coast of Havana province, have provoked the decalcification of the

calcareous rock of the caves located in a radio of 5 Km of distance. The

pictographs of Cinco Cuevas cave have been hopelessly lost due to the scaling

of the rocky surface off.

The damages of industrial type can be divided in the following

categories:

Mining: Linked fundamentally to the exploitation of quarries

and the explosions taken place during the mining process. It is also considered

the smog emanations and other gases like residual aerosols characteristic of

the extraction of petroleum, natural gas, etc.

Constructive: They are

associated to the construction of highways and the continuous vibrations taken

place by the circulation of heavy vehicles; also, it should be considered the

construction of dams and the adaptation of areas for the storage of toxic

substances, chemical, and hydrocarbons, as well as the creation of micro urban

towns near to the stations.

Agricultural: They are those related with the agricultural, cattle

raising and forest processes; as well as the deposition of stones, industrial

and crops waste, domestic garbage, etc. in the cavities. It is included the treatment

of ground for multiple agricultural activities that provoke microclimatic

changes as product of deforestation and/or reduction of the edaphic layer around

caves or rock shelters. Also the livestock breeding (bovine, porcine, etc.)

that establish room spaces in the caves to be protected of the sun and, they

rub their body against the walls with pictographs or petroglyphs, provoking

climatic and microbiological changes that in short and long term should

deteriorate the rock paintings.

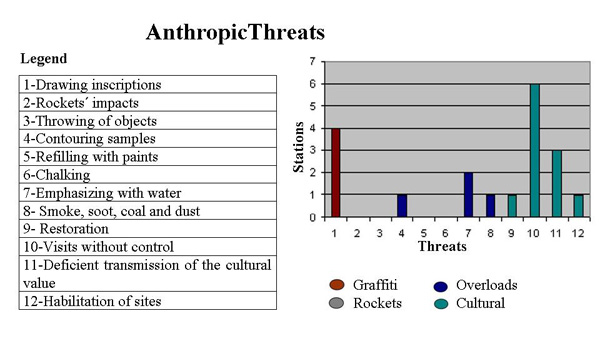

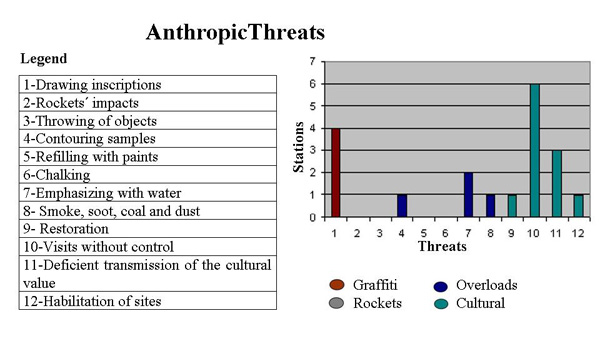

Anthropic threats

The anthropic threats represent the actions

carried out by modern man to the rock art stations and their environment in a

direct and intentional way. These constitute, without doubts, the most abundant

and devastating damages that these ancient cultural manifestations continually

receive in whole world and Cuba is included in this reality.

Graffiti: It is the damage

that has impacted the most the drawing stations in the country during the last

three centuries. It consists on "decorating" the walls of the caves

with signs of all kind, dates and drawings in occasions, which can be done with

any material as pencils, crayons, spray or diverse varieties of pigments with

acrylic and oil bases.

Rockets: It refers to two

kinds of practices with similar consequences: the first, to shoot guns toward

the drawings; and the second one, to throw all type of objects toward the walls

or the secondary formations that support the graphic manifestations.

Overload: With this term are

defined those procedures like the use of water or chalk on the pictographs

and/or petroglyphs with the intention of improving the visibility and

perception of them, but also it is included the contoured of the pictographs or

petroglyphs to define and to stand out their borders. All these actions are executed

mainly by the researchers to take the pictures or the tracing of the

registrations for its documentation. The same overload takes place when someone

light blazes or burn tires inside caves and rock shelters (2).

Cultural: The lack of

transmission to the villagers and neighbours of the information about an

archaeological site´s discovery produces the destruction or affectation of the

station because of different reasons. The researchers are the main responsible

of creating false expectations and concerns around the sites, instead of

facilitating the custody and protection.

2. It is a very habitual practice among

the peasants, beaters, fishermen and campers, to mark the walls with smoke,

soot, coal, powder and other toxic substances provoking the decalcification of

the rock due to oxidation.

|

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF

ROCK ART HERITAGE

From the beginnings of Archaeology as a science, the protection of

archaeological heritage has been one of their specialists' interests, although it

has enjoyed either successes or failures in dependence on the scientific vision

of the moments they lived.

In our country, different institutions from the beginnings of XX century

have settled down –by means of important regulations– the handling

and conservation politics of the archaeological/historical places (3); also during the

revolutionary period many laws and ordinances for the patrimonial protection

have been carried out, modified and applied. At the same time, institutions

have been created for archaeological research and the heritage management, which

have organized and carried out campaigns to rescue and salvage the places and

locations; however, the lack of control and constancy on the state,

conservation, and even on the strategies to continue the excavations of the

places, have provoked their hopeless affectation, so the situation of the

archaeological heritage is in sensitive damage at this moment (Robaina 2003).

3. Magazine of Archaeology and Ethnology, Special Number on Legislation,

year 1957; Protection of the Cultural Patrimony. Compilation of legislative texts, Ministry of

Culture, Havana, 1996.

|

The Cuban rock art patrimony is not an exception in the destruction of

its stations, that is why a strategy became necessary to discern the main

damages and threats that deteriorates it, and to design the instruments to

maintain its preservation. So a methodology was implemented able to identify at

least the main threats.

For the study it was used the Methodology for the Evaluation of the

Environmental Impact in the archaeological places, proposed by members of the

Group of Auxiliary Sciences of the Department of Archaeology in the Cuban

Institute of Anthropology, belonging to the Ministry of Science, Technology and

Environment (CITMA), in which the Indicators are evaluated for each impact:

sign, intensity, extension, moment, persistence, reversibility, recoverability,

synergy, accumulation and rhythm or periodicity.

In the case object of analysis the attention was directed in those

indicators that, in the best way, express the level and the intensity of the

affectation: the Accumulative Effect, in which the inductor agent's

action is prolonged in time, being its graveness progressively increased when

the environment lacks of elimination mechanisms. It happens, for example, in

the stations that the action of felling the surrounding vegetation provokes the

systematic loss of the coloration of drawings because of the daily incidence of

solar rays.

Synergistic Effect: It is considered when several combined impacts take

place and it is verified by the simultaneous presence of several actions. The

graveness is that the environmental incidence that takes place most be bigger

than the supreme effect of the individual ones contemplated in isolated way.

Enough examples of rock art stations exist where, due to the felling of the

surrounding vegetation, they began to face strong changes of temperature

between day and night. Fractures in the rock are the redundant consequence that

contribute to the establishment of diverse opportunists microorganisms –lichens,

mushrooms, superior plants– those which produce acids in the

photosynthesis process destroying the stony support, besides the loss of

coloration of the pictographs because of heatstroke.

Recoverability Effect: It is focused in the loss of a patrimony that is impossible

to repair, either for natural or human action. Many pictograms have been

attacked by the overwriting and graffiti’s execution that can be eliminated by

lingering and expensive chemical processes; but the operation is potentially

risky due to the alteration or mutilation of the petroglyphs, that can be

transformed into an irreparable condition.

The importance of being able to carry out the evaluation and the diagnosis

of the environmental impacts in the archaeological places consists on the

possibility of planning short trips to the different areas of the national

territory with or without risks of modifications, affectations or destruction.

The objective of those trips is to make quick and reliable valuations that

allows –by a transverse study– to know the real situation of the

study areas, or, in a random way, to select a proportional number of places

that facilitates the analysis of the approximate state of the general total

(Fernández et. al. 2009a).

During the analysis that was carried out to determine the way to proceed

for this particular case, it were randomly selected 17 rock art stations of the

37 ones that the studied region possesses, to obtain a general approached

vision of the impacts that are creating a bigger number of affectations in the

same ones, and to carry out the pertinent recommendations to eliminate or to

mitigate the damages occurred.

The systematic monitoring and evaluation of the situation of rock art stations

at a national level carried out by the Cuban Group of Rock Art Researches

(GCIAR) shows the presence of an important number of threats that ascends to

17% the industrial ones and to 83% the anthropic ones. Just 23% of the total of

274 stations reported in the country, is only protected with Monuments´

categories, and only15% is included inside the areas of National Parks and

Natural Reservations. Until now, these historical–cultural values haven´t

been taken into account for they to have the necessary exclusion or protection

areas inside those protected regions.

MUNICIPALITY

|

ROCK ART STATIONS WITH LEGAL PROTECTION

|

LOCAL MONUMENT

|

NACIONAL

MONUMENT

|

IN PROTECTION AREAS

|

WITHOUT PROTECTION

|

Guane

|

|

|

|

2

|

Minas

de Matahambre

|

1

|

|

|

10

|

Viñales

|

3

|

1

|

9

|

-

|

La

Palma

|

1

|

|

1

|

4

|

Pinar

del Río

|

|

|

|

1

|

Candelaria

|

|

|

|

1

|

Bahía

Honda

|

1

|

|

|

2

|

San

Cristóbal

|

|

|

|

4

|

TOTAL

|

6

|

1

|

10

|

24

|

|

Chart No. II.- Behaviour of

the legal protection of rock art stations of Guaniguanico Mountain Range.

|

THE EXPERIENCE IN GUANIGUANICO

MOUNTAIN RANGE. SELECTION OF THE

SAMPLE

To apply the elected methodology 17 caves and rock shelters with rock

art manifestations were selected from 3 of the municipalities that have most representativeness,

which were Minas de Matahambre, Viñales and Bahía Honda, and a cave of La Palma

municipality.

It was decided then to carry out the journey during several days with a

chronogram that admit to carry out the visits with a minimum time calculated in

2 or 3 hours by station, to evaluate satisfactorily the actions and the present

impacts. During the inspections each site was graphic and photographically

documented with the impacts detected to maintain a systematic control of the

positive or negative evolution of the same ones.

The rock

stations

Topographically the stations are located among 0 m. and 253 m. of

altitude on the sea level, establishing the limits Solapa de la Vaquería and

Cuevas del Garrafón, respectively.

In general, these manifestations of the culture material can be found in

caves –as those of Cueva del Cura and El Garrafón– that present a

few longitudinal development, among 20.0 m. of Cueva de las Manchas and more

than 700 m. of Cueva de los Petroglifos; but it reaches their maximum exponent

in 2 500 m. of Cueva de Mesa; or in big rock shelter that reach in occasions

among 2 m. and 10 m. of depth like Solapa de la Vaquería y la Cueva de Las

Manchas, respectively.

Realization

Substrates

The selection of the realization substrate in the group of stations that

we analyzed it is determined by three categories, those that can be defined as:

walls and roofs of the cavities, secondary formations (lytogenesis) and clastic

morphology (blocks of collapses).

According to the

established categories the use of the walls and roofs as substrates represent

97%, in opposition to 1% and 2% of use of the secondary formations and the clastic

morphology, respectively.

The use of the cave support from the point of view of the composition

allows settling down that the pictographs are present in the three categories

of selection of realization´s substrates, and that the petroglyphs were carried

out in the walls and roofs of the stations.

Assignment of

spaces

The assignment of spaces as a concept in the studies of the Cuban rock

art registration have gotten a special interest in the last years, starting

from the approach of some researchers that the study of this element can bring

cultural and chronological elements (Fernández and González, 2001; Fernández

2005), accepting the precepts settled down by archaeology of landscape and the

selection of the spaces where to execute the rock designs.

No.

|

NAME

|

LOCATION

|

1

|

Solapa

de La Sorpresa

|

Sierra

del Pesquero

|

2

|

Cueva

de Camila

|

Sierra

de Mesa

|

3

|

Solapa

de La Perdiguera

|

Sierra

de Sumidero

|

4

|

Cueva

de Nicolás

|

Sierra

de Sumidero

|

5

|

Solapa

de Los Círculos

|

Sierra

de Cabeza

|

6

|

Solapa

de Los Pintores

|

Sierra

de Cabeza

|

7

|

Solapa

de Quemado

|

Sierra

de Quemados

|

8

|

Cueva

de Mesa

|

Sierra

de Quemados

|

9

|

Cueva

de Los Petroglifos

|

Sierra

de Galeras

|

10

|

Cueva

del Garrafón

|

Sierra

de Viñales

|

11

|

Cueva

de Las Manchas

|

Sierra

de San Vicente

|

12

|

Solapa

de La Vaquería

|

Sierra

de San Vicente

|

13

|

Cueva

de Los Estratos

|

Sierra

de San Vicente

|

14

|

Cueva

del Cura

|

Sierra

de Guasasa

|

15

|

Solapa

María Antonia

|

Sierra

de Gramales

|

16

|

Cueva

La Espiral

|

Macizo

Pan de Guajaibón

|

17 |

Cueva Canilla II

|

Macizo Pan de Guajaibón

|

|

| Chart III.- Stations selected

for the evaluation and diagnosis of the environmental impact study in

Guaniguanico Mountain Range.

|

One of the analysed approaches was the area of execution of the

manifestations in correspondence of the incidence of solar rays in the

underground space. In the studied stations it behaved as follows: 11 places

manifest their representations in areas where the sunbeams impact directly

(thresholds areas), 2 stations show their exponents in areas where the solar rays

infiltrates by reflection (sub thresholds areas) and 4 sites exhibit their art manifestations

in areas where it never impacts the solar light (absolute darkness).

With the use of

these approaches, it could be observed in details that it is established that

the most used space was that of the sub thresholds areas, what represents 65% of

selectivity; so the presence of rock drawing in the thresholds and sub thresholds

areas is unequivocally related with pictographs. At the same time it is curious

and also proven, the fact that all the petroglyphic stations of the mountain

range had assigned the area of Absolute Darkness as space.

Evaluation and

diagnosis of the conservation

As it was explained at the beginning of this presentation, for the

evaluation and the diagnosis of the conservation´s grade of rock drawing of the

mountain range object of study, the research began using the 28 types of

actions proposed before in the mentioned study, but throughout the

investigation it was proven that these categories were insufficient, that is

why some necessary modifications were introduced and the same ones were

enlarged until a number of 34, at the same time that we were studying new areas

and that we faced the particularities of the human activity.

The evaluation of the state of conservation of the drawings allowed

verifying that the lichens, mosses or microorganisms development is the impact

that affect the sites the most, with a presence of 84%; what is in consonance

with deforestation, the action that biggest representation shows, in 70%.

GROUP

|

CATEGORY

|

ACTION

|

AFFECTED

STATIONS

|

Naturals

|

Geological

|

Expansion-contraction

of rock support

|

2

|

Collapses

|

-

|

Forming

of carbonate deposits

|

3

|

Biological

|

Construction

of insects´ honeycombs

|

2

|

Growing

of lichens, mosses and microorganisms

|

13

|

Deposition

of fecal ejections

|

2

|

Action

of moving animals

|

1

|

Climatic

|

Expansion-contraction

of rock support

|

1

|

Erosion

Eolic

|

11

|

Humidity,

evaporation, pressure and condensation

|

3

|

Changes

of water´s pH.

|

-

|

Industrials

|

Mineralogical

|

Expansion

of quarries

|

-

|

Smog

and other dusts and residual aerosols

|

5

|

Explosions

|

3

|

Constructing

|

Construction

of roads

|

1

|

Accumulation

of toxic substances and hydrocarbons.

|

1

|

Construction

of dams

|

-

|

Other

constructions

|

4

|

Agriculture and cattle

|

Construction

of corrals for breeding of minor cattle

|

1

|

Cavities´

filling with solid residues

|

2

|

Deforestation

|

7

|

Extraction

of soil and bat´s droppings

|

2

|

Anthropic

|

Graffiti

|

Drawing

inscriptions

|

3

|

Rockets

|

Rockets´

impacts

|

-

|

Throwing

of objects

|

-

|

Overloads

|

Contouring

samples

|

2

|

Refilling

with paints

|

-

|

Chalking

|

-

|

Emphasizing

with water

|

2

|

Smoke,

soot, coal and dust

|

1

|

To

enumerate

|

1

|

Cultural

|

Visits

without control

|

5

|

Deficient

transmission of the cultural value

|

16

|

Habilitation

of sites

|

1

|

Restoration

|

1

|

Total of affected stations

|

16

|

|

Chart IV.- Main

threats for the rock art drawing of Guaniguanico Mountain Range

|

Thanks to the fact that the stations of the mountain range, in a general

sense, are located in remote and distant places of urban cities and towns, the

graffiti doesn't constitute one of the most frequent environmental impacts, as

has been demonstrated by the studies carried out at national level (Fernández

and González 2001, and Gutiérrez et. al.

2007).

KIND OF ACTION

|

IMPACTS

|

Deforestation

|

Provokes

growing of microorganisms and micro flora on the paintings in the threshold

zone, due to the sunbeams.

|

Eolic

Erosion

|

Loosing

of the pigment layers in some paintings.

|

Contouring

of painting´s borders

|

Contouring,

maybe with graphite, of painting´s borders, for better recognizing.

|

Growing

of lichens, mosses and microorganisms

|

Growing

of stains that cover the paintings partial or totally.

|

Humidity,

evaporation, pressure and condensation

|

Growing

of calcite layers on the paintings.

|

Visits

without control

|

Construction

of hearths and fires that spread smoke and ashes on the pictographs.

|

Direct

action of visitors on walls and paintings.

|

Accumulation

of solid waste.

|

Expansion-contraction

of rock support

|

Cracking

and loss of the pigment layer in paintings.

|

Extraction

of soil and bat´s droppings

|

Uncontrolled

extraction and movement of archaeological evidences.

|

Construction

of corrals for breeding of minor cattle

|

Deposition

of fecal ejections that modify soil´s pH.

|

Movement

of soil.

|

Growing

of microorganisms and micro flora.

|

Deposition

of fecal ejections

|

Increasing

of acidity and degradation of walls and paintings.

|

Loss

of the color of paintings.

|

Intention

to restore

|

Contouring

samples

|

Retouching

of affected areas with clay.

|

Construction

of insects´ honeycombs

|

Formation

of concretions on walls and paintings.

|

|

| Chart V.- Impacts that affect

the rock drawing of the stations evaluated in Guaniguanico Mountain Range.

|

The impact denominated graffiti was detected in the evaluated stations Cueva

de los Estratos, Nicolás and Camila, those that coincidentally are near the

areas of more affluence of people, and they are also frequently visited by

outsiders, furtive hunters, occasional tourists and vacationers, what have

provoked adverse effects on the drawings.

The places with more variety of present kind of impacts are Cueva de Camila

affected with 12, the Cueva de la Tabla for 8, and Cueva de Nicolás for 5.

Solapa de la Vaquería with 7, and Solapa de Las Manchas affected with 6 types of impacts

are the ones that continue this lamentable list (González, et. al. 2007).

It could be proven that Los Estratos´, Camila´s and

Nicolás´ Caves, and Las Manchas´ and La Vaquería´s Rock shelter, are the stations

that present bigger risks because of the intensity of the impacts detected inside,

the ones that were evaluated with the category of "Very High

Affectation".

The bigger impact that provoked this result was the development of civil

constructions in the range between 2 and 30 m. of the stations, what has

generated violent impacts because of the dust and residual aerosols aggravated

by the arid soil movement in lingering and intense periods, and the effect of

explosions, actions linked to the partial or total deforestation of the areas, that

indirectly affected those sites.

Cueva de Nicolás' station is located next to the highway that goes to

Sumidero town, what transforms it into a public sanitary service, because it

doesn't have any mark or signal that points out its patrimonial and cultural

value.

There are also several rock art stations that have been protected for

been included in the areas belonging to National Parks or Reserve of Biosphere

that have Guard Parks or Guard Forests systems. The efforts that have allowed a

better protection of those stations, have being proving the remarkable decrease

of the affectations to pictographs and petroglyphs (Fernández et. al. 2012).

|

Fig.

2.- Graph of the types of natural threats that affect the rock art stations.

|

In this sense the cavity well-known as Cueva de Mesa in Gran Caverna de

Santo Tomás, is the only one that has specialized guide service, for being located

in the territory belonging to Viñales National Park, and in the properties of

the former National School of Speleology, that had an obligatory access through

a Control Post.

The

tourist exploitation of Gran Caverna de Santo Tomás system began at the end of

the nineteenth decade, for that reason new entrances to the cavity were created

to facilitate the tourism journeys. Unfortunately, the evaluation that was

carried out to determine the possible affectations that the station would

receive it was incorrect, accentuated by the absence of a systematic monitoring

and by the out of control in the access, linked to the direct contact of

irresponsible excursionists and the increase of the continuous flow of air from

the cavity, what has provoked the irreparable deterioration of the petroglyphs.

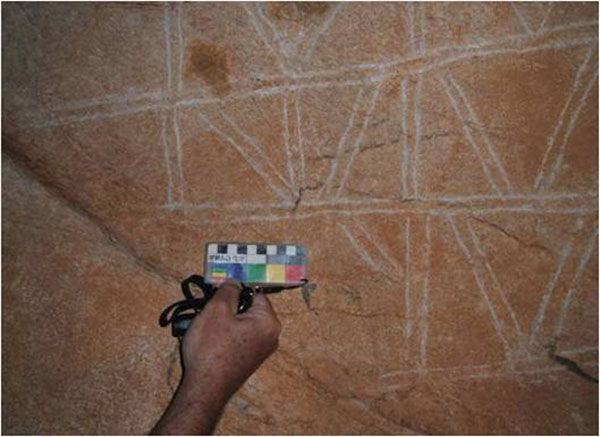

A community of investigators of the county tried to restore some of the

engravings applying some splashes of carbonate sand, obtained from the area

around of the petroglyphs, by the using of a dental brush like a rustic aerosol

for that, and the using of a sharp instrument to emphasize them.

|

Fig.

3.- Graph of the types of industrial threats that affect the rock art stations.

|

This inadequate procedure didn't have the registration and documentation

of the original petroglyphs, neither of the elaboration of the file that

documented the whole process with the description of the applied procedure.

This action introduced to the painting mural an unimaginable number of

microbiological and microclimatic dangers that cannot be valued nowadays; also

the completely perceptible morphological modifications.

|

Fig.

4.- Graph of the kind of anthropic threats that affect the rock art stations.

|

The

institutions involved in the research, conservation and safeguards of the

cultural and natural patrimony are the direct responsible of making that the

laws that protect our heritage be worth at every level. They also should unite

their efforts to achieve the execution of the effective dispositions and to

correct or complete the corresponding documentation for their correct safeguard.

Hence,

it can be confirmed that the state of conservation of the rock drawings present

in the stations of Guaniguanico Mountain Range, are classified in the category

of "High Affectation"; that is why it is imminent the necessity that

the structures of the municipal governments of this region, consider this

patrimony as one of the most fragile cultural resources and in consequence they

act to protect it.

No.

|

NAME

|

AFECTATION GRADE

|

1

|

Solapa de La Sorpresa

|

3

|

2

|

Cueva de Camila

|

1

|

3

|

Solapa de La Perdiguera

|

2

|

4

|

Solapa de Los Círculos

|

2

|

5

|

Solapa María Antonia

|

4

|

6

|

Solapa de Los Pintores

|

4

|

7

|

Solapa del Quemado

|

3

|

8

|

Cueva de Mesa

|

1

|

9

|

Cueva de Los

Petroglifos

|

4

|

10

|

Cueva del Garrafón

|

3

|

11

|

Cueva de Las Manchas

|

1

|

12

|

Solapa de La Vaquería

|

1

|

13

|

Cueva de Los Estratos

|

1

|

14

|

Cueva del Cura

|

3

|

15

|

Cueva de Nicolás

|

1

|

16

|

Cueva Canilla II

|

2

|

17

|

Cueva La Espiral

|

4

|

|

Chart

VI.- Grade of general affectation for station.

Legend:

Very High Affectation (1), High Affectation (2), Moderate (3), and Slight Affectation

(4)

|

|

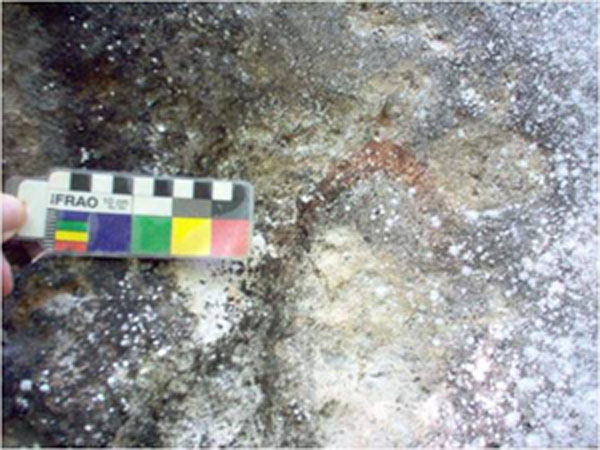

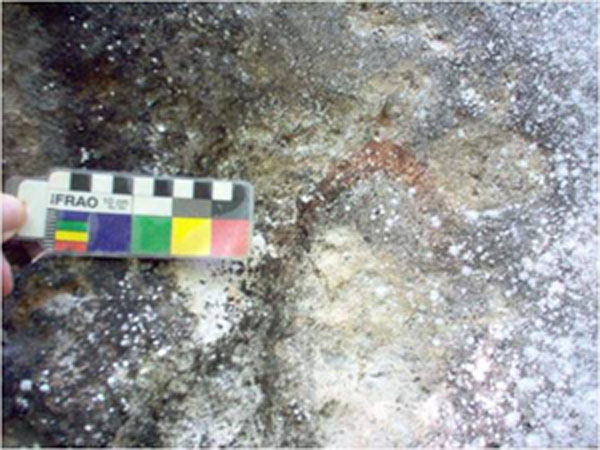

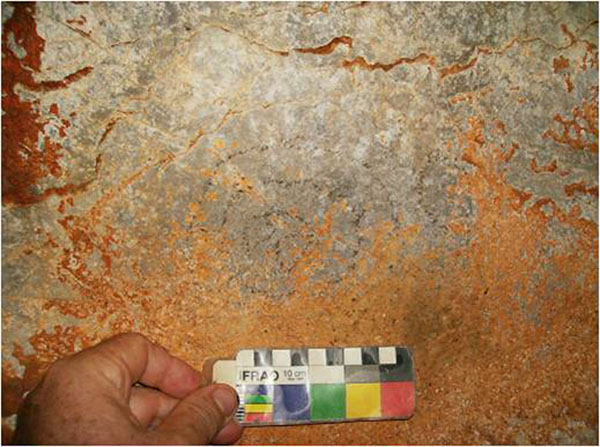

Fig. 5.- Solapa de la Sorpresa in Sierra del Pesquero.

Painting affected by the growth of microorganisms on

the wall (files of GCIAR).

|

|

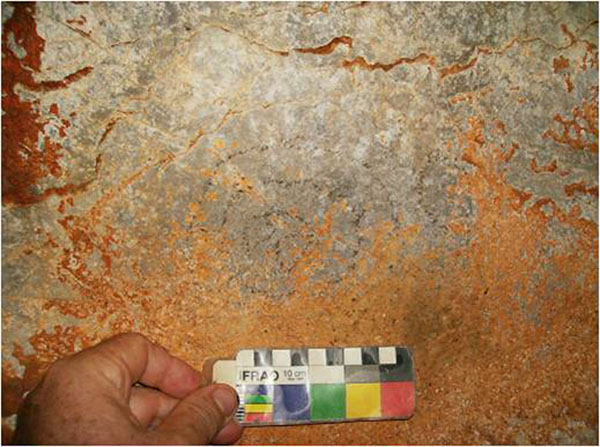

Fig. 6.- Cueva La Espiral in

Macizo de Guajaibón.

Formation of

deposits of carbonates (the authors' files).

|

|

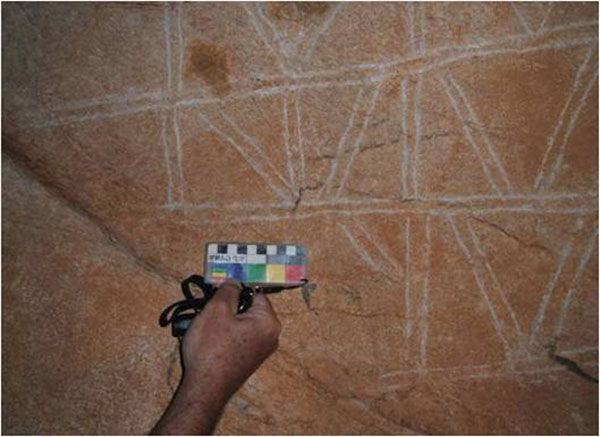

Fig. 7.- Cueva de Mesa in Gran

Caverna de Santo Tomás.

Contouring

restoration by incised lines (files of GCIAR)

|

|

Fig. 8.- Cueva de Nicolás

in Sierra de Sumidero.

Growth

of microorganisms on the rock support (files of GCIAR).

|

|

Fig. 9.- Solapa de los Círculos in

Sierra de Cabeza.

Development of insects´ honeycombs (files of GCIAR).

|

CONCLUSIONES

The impacts that bigger number of affectations are creating in the visited stations, are the wrong antrophic manipulation of the ecosystem around them that provoke secondary effects such as the presence of microorganism, plants, ans zoological opportunist species that irreversibly damage ythis millennial heritage.

The country has the legal corpus that should guarantee the protection ans conservation of the Cultural Heritage, but regrettably it doesn´t mention the rock art as the specifities included, such as architectural elements, among otrhers. In this sense, and taking into account the proposals resulted in the International Consulation of Specialis´t in Study, Documentation and Conservation of the Rock Art, celebrated in Valmónica in 1981, we are agree with the approach that the necessity to establish a corpus of particular laws, for the heritage protection, conservation, administration, use and handling, is unavoidable.

The institutions involved in the research, conservation and safeguards of the cultural and natural heritage are the direct responsible of applying the laws that protect our heritage, and of achieving the execution of the dispositions for their correct preservation.

—¿Preguntas,

comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

Cómo citar este artículo:

Ortega, Fernández Racso; Morales Valdé, Dany;

Hernández Rodríguez, Dialvys y Villate Cué,

Victorio

An analisis of the evaluation and diagnostics to environmental

impacts in rock art stations of Guaniguanico Montain Range, Cuba

En Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/guaniguanico.html

2013

REFERENCIAS

Alonso, E. M. (1995): Fundamento

para la historia del Guanahatabuey de Cuba. Editorial Academia. La Habana.

Alonso, E. M., C. Rosa, C. Guanche, H. Carmenate, D. Rodríguez, M. R. González y E.

Blanco. (2004): “Pinar del Río: Arte

Rupestre”, CD-ROM II Taller Internacional

de Arte Rupestre, La Habana.

Comité Estatal de Estadísticas (1981): Estudio sobre la

Cordillera de Guaniguanico. Censo de

población y vivienda. Marzo de 1981. Instituto de Demografía y Censos.

36pp.

Corvea, J. L.; R. Novo, Y. Martínez, I. de Bustamante y J.

M. Sanz, (2006): El Parque Nacional Viñales: un escenario de interés geológico,

paleontológico y biológico del occidente de Cuba. En Trabajos de Geología, Univ. de Oviedo, 26: 121-129.

Dirección de Patrimonio Cultural (1996): Protección del Patrimonio Cultural.

Compilación de textos legislativos, Ministerio de Cultura, La Habana.

Fernández, R. y J. B. González, (2001):

Afectaciones antrópicas al arte rupestre aborigen en Cuba. Rupestre Revista de Arte Rupestre en Colombia, Año 4, No. 4,

Bogotá.

Fernández, R. (2005): “El registro gráfico rupestre como fuente de información Arqueológico-antropológica.

La Caverna de La Patana, Maisí, Guantánamo, Cuba”. Tesis en Opción

al Título Académico de Máster en Antropología Sociocultural. Facultad de

Filosofía e Historia, Universidad de la Habana (inédito).

Fernández, R.; D. Morales; Y. Cordero; J. G. Martínez; V. Cué; J. B

González; L. Torres; S. T. Hernández; H. Carmenate; J. A. Amorín; I. Hernández

y D. Gutiérrez; (2009a): La evaluación y el diagnóstico del estado de conservación del

patrimonio arqueológico de Cuba.

Fernández,

R., J. B. González y D. A. Gutiérrez (2009b): History, Survey, Conservation, and Interpretation of Cuban Rock

Art. [with translation by Michele H. Hayward]. In Rock Art of the Caribbean. Editores Michele H. Hayward, Lesley-Gail Atkinson y Michael A. Cinquino. The University of Alabama Press, Colección Caribbean

Archaeology and Ethnohistory Series: 22 - 40. Tuscaloosa.

Fernández, R.; D. Morales; D. Rodríguez y V. Cué (2012): Arqueología y turismo en Cuba.

¿Simbiosis para el desarrollo sostenible? Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi “Ciencias Humanas”, Belem,

Brasil. (En prensa).

González, J. B.; R. Fernández, D. Gutiérrez, H.

Carménate, Y. Chinique y D. Rodríguez (2007) Reporte del trabajo

realizado en 13 de las estaciones de arte rupestre de la provincia de Pinar del

Río. Proyecto de evaluación y diagnóstico del patrimonio sociocultural de

Cuba. Archivos del Dpto. de Arqueología del Instituto Cubano de Antropología,

La Habana.

Gutiérrez, D.; R. Fernández,

y J.

B. González. (2007):

La conservación del patrimonio rupestrológico cubano. Situación actual y

perspectivas. En Boletín del Gabinete de Arqueología, Oficina del Historiador de la

Ciudad, Año X, (X): 107-124.

Junta Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología (1957): Número

Especial sobre Legislación, Revista de la Junta Nacional de Arqueología y

Etnología, Época 3ra., La Habana.

Robaina, J. R; M. Celaya; O.

Pereira; R. Rodríguez (2003): Gestión y

manejo de recursos y valores arqueológicos patrimoniales de la República de

Cuba. Monografía (inédita). Fondos Documentales del Instituto Cubano de

Antropología. Resultado de Investigación.

|

![]()