|

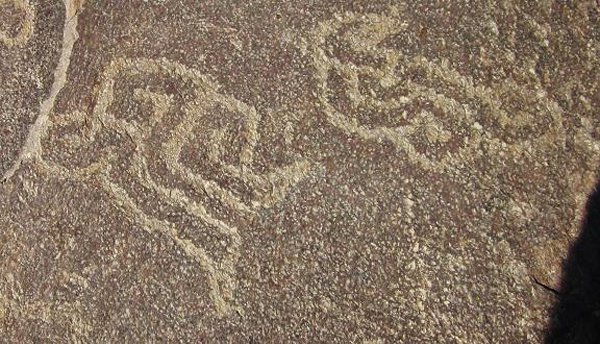

| Figure 1. The petroglyphs on the

Piedra del Sol, Simbal, Peru. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on the illustration by Zevallos Quiñónez (1990: Fig. 13). |

2) Lúcumar

I first learned of this petroglyph site

in 2009 when I found a photograph on the internet (web site no longer

available) with a text which read: Los

petroglifos de Simbal. Cruzando el Río Lucumar y frente a los

linderos del caserío de Cajamarca, un simbalero, hace 3.500 años, nos ha dejado

el testimonio de su arte (date and author unknown to me). Interestingly, the

2009-text referred to other rock art sites in this valley and therefore I will

return to this text further on. The site is not mentioned in the Inventario Nacional by Rainer Hostnig

(2003). Later, I found the publication by Castillo Benites (2008/2009) on the

internet (not offering the illustrations; these were forwarded by him to the

general public via the internet much later, in 2013).

Because of the mix of loose boulders and fixed outcrops at this site the factual number of boulders/panels is rather confusing. Castillo Benites mentions ‘six rocks or panels’ (seis soportes) with petroglyphs at Lúcumar, although he actually illustrates 13 panels (2008/2009: Láminas 4 to 12). Rocchietti (2012), who only discusses the LUC-004 complex, claims that two the two rocks that she describes (Bloque Mayor and Bloque Menor, respectively comprising the following panels: LUC-004ABCDEF and LUC-004G) are actually part of one and the same outcrop and therefore I follow her claim. Having said all this, it is surprising to see that in fact there are ten boulders/outcrops at this site with altogether 16 panels; three of which (LUC-001, LUC-003 and LUC-004F) have not been described by Castillo Benites.

|

Figure 2. MSC-Style petroglyphs on

Boulder LUC-008, Lúcumar, Simbal, Peru.

|

|

Figure 3. Possible MSC-Style

petroglyphs on Boulder LUC-008, Lúcumar, Simbal, Peru.

|

|

Figure 4. Petroglyphs on Boulder

LUC-010, Lúcumar, Simbal, Peru.

|

Newly Recorded Rock Art Sites

Interestingly,

Castillo Benites (2008/2009), while referring to Disselhoff (1955: 68), relates

of two other possible rock art sites in the Simbal region. 1: Se

cuenta con las referencias descriptas por Disselhoff en la década del

cincuenta. Según relata, había escuchado comentarios acerca de la entrada de

una mina de plata abandonada en la que se encontraban varias

"figuras". 2: La misma se

ubicaría en el trayecto del camino entre Simbal y Sinsicap, pero fue en vano su

esfuerzo por localizar el sitio en la parte alta del Valle de Moche.

Cerro Prieto is the name of a small hill (cerro) 4.8 km north of Simbal and also of a very small hamlet at the east foot of that hill. ñary is a ‘caserío’ some 9 km NNE of Cerro Prieto (actually, the purported rock art site - en el camino a ñary - can be located anywhere between Simbal and ñary). Cerro Prieto is also one of the most densely populated ‘caseríos’ in the Simbal District (apart from Simbal). Collambay is a hamlet 2.5 km NE of Cerro Prieto. Near Collambay is a very large round boulder with, at its bottom, a very large (anthropic?) hole (large enough for an adult to sit in). This boulder might be the site referred to by Rocchietti as the Piedra Huequeada de Mucha (2012: 6).

|

Figure 5. Petroglyphs on Panel

CPR-003C, Cerro Prieto, Simbal, Peru.

|

Boulder CPR-004 is located

directly north of Boulder CPR-003. On its slightly sloping upper surface are

the faint remains of a possible ‘head’ petroglyph with dots for facial features

and a number of curvilinear designs. The vertical north side might have some

faint lines. Boulder CPR-005 is

located a short distance from the previous two and its west sloping surface

seems to have one image of a (very faint) zoomorph with a curled tail and

other, even fainter markings.

The village square of Simbal also has a painting of a petroglyph site that is labelled Piedra la Paloma (also called La Piedra de Chacchito de la Paloma locally). It proved to be the petroglyph that I found earlier on the internet, where two photos of the stone, labelled Simbal - Valle Moche, are shown in a web page of the Proyecto Arqueológico Ventarrón - Collud. I wrote to Dr. Ignacio Alva Meneses, director of the Huaca Ventarrón Archaeological Project in Lambayeque, who was so kind to bring me in contact with Mr. José Carlos Orrillo of Trujillo who told me (2012: pers. comm.) that a friend of him discovered this stone in 1998. He called the stone the Piedra del Aguila or Petroglifo de Simbal, but because of the painting in the village, I prefer to maintain the name Piedra la Paloma, which is also used by Rocchietti (2012: 6).

The vertical west face of the Piedra la Paloma (Figure 8) bears a clear design of a MSC-Style profile head with an eye with an eccentric pupil, a downward curving mouth and a typical row of three triangular appendages on the head that most likely represents some kind of headgear. Emerging from the back of the head is a feature of three parallel bands (one ending in a short spiral) that may represent a (fish?) tail (compare this with a similar petroglyph at Alto de la Guitarra). Hovering over the head is another petroglyph that may represent part of an MSC-Style head, while in front of the head are further lines. There may be some images on top of the stone, but these could not be ascertained.

|

Figure 6. MSC-Style petroglyphs on

the Piedra la Paloma, Simbal, Peru.

|

|

Figure 7. MSC-Style petroglyphs on

the Piedra la Paloma, Simbal, Peru.

|

|

Figure 8. MSC-Style petroglyphs on

the Piedra la Paloma, Simbal, Peru.

|

5) Río La Cuesta

Until recently no rock art had been recorded in the valley south of Simbal. However, in the stretch of four km of the river valley between the village of Simbal and the confluence of the Río La Cuesta with the Río Moche, at least one petroglyph boulder has been recorded by an anonymous person who once posted some photographs on the internet. With some trouble I could trace the spot with Google Earth. The petroglyphs appear on one of the many large boulders at the foot of a low ridge. SSW of this site, in Moche, is the rock art site of Menocucho described by Ventura & Quiros (2004).

|

Figure 9. Petroglyphs on a boulder near the Río La

Cuesta, south of Simbal, Peru.

|

Conclusion

It is not at all unexpected that new rock art sites are being discovered in the Andes. This chain of high mountains and dry coastal deserts has a long history of emerging and declining cultures that all left their marks; also on the rocks. The area around Simbal is no exception. Therefore, also the rock art repertoire around Simbal will reflect the influence of those cultures. However, it is very difficult to assign individual rock art images to a specific culture.

Acknowledgements

This update

could never have been written without the kind assistance of Mr. Hever Vargas

Pando of Simbal who enthusiastically guided us to Chachit and Lúcumar. We are

also grateful to him for showing us his collection of photographs and for

additional information. I am indebted to Dr. Ignacio Alva Meneses, director of the

Huaca Ventarrón Archaeological Project in Lambayeque for his help in tracing

the origin of two photos of the Piedra la Paloma in the web site of the Huaca

Ventarrón Archaeological Project and especially to Mr. José Carlos Orrillo who has been so kind to

share photographs and information with me about this rock art site. Two of his

photos (Figures 6 and 7) have been included in this paper with his kind

permission. We are also grateful for all the local people who helped us

on our way and for permission to enter their properties. Last but not least I

thank my wife Elles for her ongoing support, in the field and at home.

![]()

—¿Preguntas, comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

Cómo citar este artículo:

En Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/simbalpetroglyphart.html

2014

Ver comentario de Daniel Castillo Benites y réplica del autor

References

Castillo Benites, D. S. 2013. Identifican 40 pinturas rupestres en la localidad de Paranday. In: Lista

Arqueologia Peruana.

-2008/2009. Petroglifos del Distrito de Simbal, valle de Moche. Lista Arqueología en DePeru.com. En: Revista Museo de Arqueología Universidad

Nacional de Trujillo No. 11; pp. 145 - 158. Trujillo.

-2006. Pictografías en la Quebrada del Higuerón, Valle de Chicama, Perú. En Rupestreweb: http://www.rupestreweb.info/higueronperu.html

Romero Marines, A. 2012. Tour Simbal. Recursos Arqueológicos y Recursos Turísticos.

Information on

the internet: Tu Pekeña Travieza.

Comentario al artículo “An update of the petroglyph art near Simbal, Río Moche, North Perú”

Por Daniel Castillo

Benites d_castillo_b@hotmail.com

En relación al trabajo de van Hoek, Maarten. An update of the petroglyph art near Simbal, Río Moche, Norh Perú, publicado en Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/simbalpetroglyphart.html 2014, me veo en la obligación moral de contestar al menos algunas de las afirmaciones que presenta y formular sugerencias que contribuyan a un avance cuali-cuantitativo en las investigaciones del arte rupestre peruano.

El artículo mencionado basa su aporte en la crítica de dos trabajos, uno de mi autoría (Castillo: 2008/09) y el otro de A.M. Rocchietti (2012).

En primer lugar deseo destacar que ambos investigadores hicimos nuestro aporte desde una gran idoneidad, experiencia de campo y formación en la especialidad, es más, cuando apareció el artículo de la Dra. Rocchietti comprendí que no tuvo acceso a mi trabajo y lo adjudiqué a un desliz del equipo que la acompaña, es decir, que por sobre todo disfruté del texto y de reconocer la fuerza que imprime a todas las actividades que promueve en el Perú.

En segundo término y limitándome a lo nodal de las críticas que formula van Hoek, diré que es risible la presentación de discrepancias entre las coordenadas que brindamos para los sitios “La Piedra del Sol” (Castillo) y Lucumar (Rocchietti) con relación al Google Earth, cuando el autor ni siquiera hace un intento para los hallazgos que realiza y describe en Cerro Prieto, para “evitar daños o vandalismo”, lo que constituye al menos una ingenuidad de su parte, y además pone de manifiesto la ausencia de trabajo y gestión con las comunidades locales para evitar que tales eventos pudieran ocurrir.

Respecto al petroglifo “La Piedra del Sol”, en ningún punto del artículo tratado lo adscribo al “período Chavín” como afirma van Hoek, y de hecho lo refiero al formativo tardío. Asimismo, el neologismo “MSC-Style” que le pertenece y sigue en sus publicaciones, es un concepto que afirma estar dirigido a “anular la incorrecta y consecuentemente no deseada etiqueta Chavin”. Por mi parte sostengo que se trata del reemplazo de una etiqueta por otra y que además está mal definida. La literatura en metodología arqueológica es riquísima en trabajos sobre la definición de estilos, fases, facies y demás unidades integrativas, y aún como hipótesis de trabajo, integrar en un solo estilo las producciones Manchay, Sechín y Cupisnique constituye una simplificación extrema que no merece mayores comentarios.

Por otra parte, llama la atención que el autor publique un dibujo del petroglifo Piedra del Sol realizado sobre una ilustración de Zevallos Quiñónez, ya que visitó el sitio, describió los motivos y de seguro pudo brindarnos una versión mejorada con los equipos fotográficos que usó para mostrarnos, por ejemplo, el detalle de un petroglifo de Cerro Prieto.

En cuanto a Lucumar, cabe destacar que la publicación completa estuvo a disposición del público en 2009 (Revista del Museo de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia - Trujillo), y lo que el autor refiere sobre los hallazgos que realizó en Internet (2008/2009 y 2013) corren por su cuenta, la información estuvo disponible desde la fecha de edición mencionada.

En arqueología, y por consiguiente en arte rupestre, las técnicas de registro y documentación se eligen o adaptan a la características que los sitios presentan, quizás la falta de formación en esta disciplina condujo al autor citado a encontrar confusa la presentación del sitio en soportes y paneles, una técnica por demás aceptada y aplicada, al igual que el empleo del microscopio en el trabajo de campo, la guía Munsell de colores, y otras herramientas de trabajo que nos permiten realizar estudios de técnicas de ejecución, pátina y demás, las que en algunas oportunidades conducen al descarte de motivos y/o soportes que corresponden a “trabajos modernos”. En este caso en particular, me acompañaron y estuvieron a cargo de los estudios mencionados, la Lic. María Susana Barrau (Universidad de Buenos Aires) y el Lic. Ilder Cruz (Universidad de Trujillo).

Cada aporte al conocimiento de un sitio arqueológico es una invitación a revisar la evidencia reunida, y dado que recorremos en forma periódica los sitios registrados y documentados, a fin de verificar aspectos relativos al estado de conservación e implementación de planes de gestión, aprovecharemos la próxima ocasión para realizar observaciones adicionales. Por otra parte, también contrastaremos nuestros archivos con el material editado, porque es real que en ocasiones se invierten las ilustraciones o deslizan errores que pueden fácilmente subsanarse.

De todas formas deseo dejar en claro que cuando un estudioso se refiere al trabajo de otros profesionales en los términos en que van Hoek lo hace, lo mínimo requerido desde la ética y hasta del sentido común, es proveer al lector de los elementos de juicio necesarios para que pueda formar su opinión al respecto. Es obvio que las afirmaciones sobre lo que la Dra. Rocchietti y yo conocemos y manejamos sobre el tema que nos ocupa, caen en un ámbito mágico-religioso, y en este sentido el autor se arroga facultades divinas. Ahora bien, cuando se refiere a dibujos completos, sin distorsiones de cualquier tipo y que hagan justicia a las evidencias que sostiene haber registrado y documentado, es lógico esperar que muestre su aporte más allá de las palabras, con dibujos y fotografías que sustenten sus dichos, más aún cuando el artículo reseñado es una edición electrónica, de tal forma que es ridículo pensar que sufrió limitaciones de espacio, tan comunes en obras y publicaciones periódicas. En síntesis, este proceder sólo arroja un manto de duda acerca de la intencionalidad detrás de las observaciones realizadas, y citamos algunos ejemplos haciendo la salvedad que el artículo no está paginado: “su dibujo debe rotarse 180°” -“su dibujo es incompleto”- “su dibujo de este amplio ‘head’ petroglifo es inexacto” -“ligeramente distorsionado”- “pero debe rotarse aproximadamente 30° en el sentido contrario a las agujas del reloj” -“este dibujo no hace justicia al especialmente único petroglifo con una combinación ornito-zoomorfa. Otro petroglifo encima del pájaro claramente representa a un zoomorfo y no a una mancha amorfa”.

En este contexto, nos sorprende en primer lugar al reportar los soportes de Cerro Prieto con una detallada descripción de los motivos grabados, y omitiendo la presentación de los dibujos respectivos, y en segundo lugar, que decida informar sobre los petroglifos de Piedra la Paloma y Río La Cuesta, ya que los datos que brinda son de segunda mano y emplea fotografías de terceros, de tal forma que presenta dibujos realizados a partir de esas imágenes, e incluso en el segundo caso, agrega apreciaciones sobre la ubicación del sitio realizadas a través del Google Earth, y se vale de fotografías para estimar las dimensiones y probable orientación geográfica del soporte. Es de lamentar que esta información tan válida para programar una salida al campo con la finalidad de registrar y documentar tales expresiones, se incluyera en un artículo de revisión del trabajo de otros investigadores, ya que sin lugar a dudas este proceder no se condice con un abordaje científico de la materia.

En la conclusión del trabajo, el autor reseñado alude a la dificultad en asignar las imágenes del arte rupestre a una cultura específica, y nosotros ampliamos el concepto, y sostenemos que es una tarea imposible para aquellos que desconocen los contextos arqueológicos respectivos, y muy especialmente la iconografía predominante en las sociedades que nos precedieron, en este caso, en la ocupación del valle de Moche.

van Hoek sostiene “Castillo adscribe los motivos de LUC-010 a la cultura Moche. Esto puede ser correcto, pero prefiero manejar este asunto más cuidadosamente y asentar que otras culturas, como Salinar o Chimú, también pueden ser responsables por esos petroglifos”. De nuevo enfrentamos apreciaciones sin una base argumentativa sólida, ya que la vía correcta pasa por el análisis, evaluación, aceptación o rechazo de la información brindada en el texto.

Por último y citamos: “En conclusión, de lo que podemos estar seguros es de que el arte rupestre en las inmediaciones de Simbal data desde el período formativo al período intermedio tardío”, afirmación que de nuevo nos sorprende, ya que pasa por alto la información que brindo acerca de la representación de la flor de la cantuta, motivo ampliamente difundido en el ámbito incaico, un dato que complementamos con noticias etnohistóricas.

En síntesis, el arte rupestre que estudiamos es sólo una pequeña porción del testimonio material de los grupos humanos que construyeron sociedades y espacios a lo largo de la costa norte peruana. En tal sentido, el abordaje es siempre desde la arqueología, con las técnicas de registro y documentación desarrolladas a tal fin, y con un conocimiento profundo de los contextos arqueológicos y paisajísticos asociados.

En los últimos 10 años se multiplicaron las investigaciones sistemáticas del arte rupestre de la zona tratada, con el aporte de científicos que trabajan con técnicas y metodologías cada vez más refinadas y enriquecidas a través de la participación en congresos nacionales e internacionales, que proveen ámbitos magníficos para la transmisión e intercambio de conocimientos.

En definitiva, esta es mi manera de decir que la opción seria y viable es construir desde la ciencia arqueológica, y que ya no caben reportes sobre la base de fotografías, datos e incluso informes completos que se obtienen “en donación” por parte de terceros, sin la debida confirmación de los datos en el terreno, como así tampoco aplica el recurso de enviar a guías locales con cámaras fotográficas a recorrer sitios, o acosar por mail a investigadores, universidades, o editores reclamando información inédita, que está en prensa o en proceso de elaboración.

Las últimas palabras las dedico a agradecer a la Dra. Rocchietti por su incansable labor en el Perú y Argentina, trabajos imposibles de resumir en estas líneas, pero que construyen un puente de conocimiento y un lazo que nos une también en el afecto. Sostener como afirma van Hoek que la Dra. Rocchietti desconoce la iconografía del formativo o del período intermedio temprano, es una herejía que no merece mayor comentario.

Gracias por la atención

Cordialmente,

Daniel

Castillo

DESCARGAR AQUÍ El pájaro de Simbal (valle de Moche, Perú). Ana Rocchietti

DESCARGAR AQUÍ Petroglifos del distrito de Simbal, valle de Moche. Daniel Castillo Benites

Réplica al comentario del artículo “An update of the petroglyph art near Simbal, Río Moche, North Perú”

Por Maarten van Hoek rockart@home.nl

En respuesta al comentario de Castillo Benites:

Primero: Mi artículo sobre Simbal que he publicado en Rupestreweb (2014) es exactamente lo que dice en el título: una actualización. Una actualización reexamina las fuentes disponibles y -cuando es necesario- reajusta los resultados; basando todas las correcciones en las investigaciones en el campo. Nunca fue mi intención ofrecer un inventario completo ni científico, ni presentar en detalle un texto y una descripción gráfica completa (con fotografías y/o dibujos de todos los soportes).

También es demasiado fácil de Castillo decir que su publicación completa de Simbal (2009) estuvo a disposición del público en el año 2009. El año de publicación no significa que la publicación este a disposición del público en todo el mundo inmediatamente. Quizas por este razón Castillo publicó su 2009-trabajo, pero sólo el texto - sin ilustraciones, en el internet al 15 de junio 2010 (http://lista-arqueologia.de peru.com/2010/06/arqueologia-petroglifos-del-distrito-de.html). Sin embargo, Castillo distribuyó las illustraciones de su trabajo (Anexos) como archivo adjunto (PDF) en un correo electrónico mucho más tarde, en 2013.

Para mí, es totalmente irrelevante si alguien tiene un título académico o no, tiene una gran experiencia o no. Lo único que importa (para mi) es el resultado; lo que se ha publicado (en papel o electrónicamente). Este resultado (el artículo: texto y los dibujos correspondientes) puede ser leído y comentado por lectores críticos. Invito a todos los lectores de Rupestreweb a leer mi trabajo (agradezco a Castillo por compartir una traducción en Español con los lectores de Rupestreweb) y juzgar si he escrito algo incorrecto.

Entretanto, hay un artículo de Castillo (2009) con un poco de información incorrecta. Anticipo que una publicación científica ofrezca la información correcta, pero demostró que el artículo de Castillo (2009) no era exacto en cuanto a algunos asuntos. Consecuentemente, a veces me parece necesario hacer correcciones en el texto y/o en las ilustraciones. Para mi no importa quién hace las correcciones. ¿Quién me impide de corregir algo? Castillo tendría que agradecer que alguien hace estas correcciones.

La única cosa en que Castillo es correcto es que yo no tengo ninguna formación académica en la arqueología: tengo formación académica en geografía. Sin embargo, en lo que respecta a arte rupestre tengo absolutamente la experiencia en el campo: desde 1975. Y desde 1982 he publicado más de 80 artículos y libros sobre arte rupestre mundial (http://andeanrockart.webklik.nl/page/bibliography).

Segundo: Sin embargo, ¿por qué a mi? ¿por qué ahora? ¿por qué Castillo considera sólo mi obra de Simbal (2014) y por qué sólo ahora (después de muchas otras publicaciones de mi parte)?

¿Por qué ahora mi trabajo de Simbal (2014) ofrece un poco de crítica al trabajo de Castillo (2009)?

Además, muchos investigadores de arte rupestre utilizan fotos, diapositivas y dibujos de otros investigadores, sin nunca haber visitado los lugares (unos ejemplos: Núñez Jiménez 1986: 443 - Pampa Calata; Hostnig 2003: muchos sitios; Linares Málaga: muchos sitios etc.). También en estos casos, estos investigadores de arte rupestre nunca han investigado estos sitios in situ, ni la comprensión de la arqueología de estos lugares. Además, algunos de estos investigadores -como yo- no tienen formación académica en la arqueología (pero para mi, no importa). Por lo tanto, es muy extraño que Castillo sólo critique mi trabajo de Simbal (y mi persona).

Desde el año 2000 he escrito 38 artículos y libros sobre arte rupestre Andino, publicados en diferentes medios de comunicación (Rupestreweb, Rock Art Research, Boletín de SIARB, etc. Ver: http://andeanrockart.webklik.nl/page/bibliography y nunca Castillo tenía ningún comentario sobre mis publicaciones, tampoco sobre mi trabajo de Tomabal en "su" zona, La Libertad: VAN HOEK, M. 2007. Petroglifos Chavinoides cerca de Tomabal, Valle de Virú, Perú. Boletín de SIARB, Vol. 21, pp 76-88. La Paz, Bolivia. ¿Por qué ahora de repente? ¿Por qué en este caso (Van Hoek 2014) el 2009-artículo de Castillo está un poco corregido?

Tercero: Quisiera preguntar a Lic. Castillo (con su experiencia en el campo y con su formación académica en arqueológica; trabajando con técnicas y metodologías cada vez más refinadas y enriquecidas a través de la participación en congresos nacionales e internacionales) de explicar las siguientes cosas:

1) ¿Por qué Castillo ha publicado un trabajo sobre Simbal (2009) en qué tres piedras/paneles con petroglifos faltan en su lista de Lúcumar? ¿Es posible que yo tenga una mejor experiencia/experticia en el campo?

2) ¿Por qué Castillo ha publicado un trabajo sobre Simbal (2009) en que algunos dibujos de petroglifos de Lúcumar no son correctos? ¿Es posible que yo tengo una mejor experiencia/experticia en hacer dibujos?

¿Castillo necesita dibujos o fotografías o información addicional? En mi trabajo de Simbal (2014) hay una dirección de correo electrónico: alguien me puede pedir información adicional. También Castillo podrá solicitar fácilmente a través de correo electrónico para obtener información adicional, en lugar de atacarme inapropiadamente y en público.

Además, el neologismo “MSC-Style” es de hecho un acrónimo que no está mal definida, como dice Castillo. He escrito un libro de 221 paginas con 174 illustraciones para definir y acalarar el acrónimo (Van Hoek 2011).

¿Por qué es necesario para Castillo para usar tales palabras negativas y oraciones que considero como un ataque personal (porque ellos no tienen nada que ver con el contenido de mi papel)?

Cuarto: ¿Y por qué es necesario para Castillo utilizar tales palabras y frases negativas que considero como un ataque a mi persona (porque estas palabras y frases no tienen nada que ver con el contenido de mi papel)?

Ejemplos: herejía; risible; falta de formación; el autor se arroga facultades divinas; acosar por mail a investigadores; acosar por mail a universidades; acosar por mail a editores; reclamando información inédita, que está en prensa o en proceso de elaboración.

Acosar (molestar, atufar, crispar, desagradar, disgustar, encalabrinar, encocorar, enfadar, enojar, exacerbar, exasperar, fastidiar, hartar, hostigar, impacientar, indignar, irritar, provocar a) es un palabra impropia de Castillo. ¿Por qué? Porque siempre he pedido informacion cortésmente.

Sobre todo la ultima acusación de Castillo a mi persona es falsa y una decepción: Nunca he reclamado información inédita; siempre he pedido información cortésmente y nunca he usado (a sabiendas) información inédita sin permiso personal del autor.

Las últimas palabras: también es fácil para Castillo poner -de una manera negativa- las cosas fuera del contexto.

Un ejemplo pungente: Castillo ha escrito en su réplica: Sostener como afirma Van Hoek que la Dra. Rocchietti desconoce la iconografía del formativo o del período intermedio temprano, es una herejía que no merece mayor comentario. Con esta frase Castillo afirma que yo insisto en que la Dra. Rocchietti no esté familiarizada con la iconografía del Período Formativo o el Período Intermedio Temprano.

Esta réplica de Castillo es completamente falsa. ¿Por qué? ¡Porque Castillo usa una frase incompleta! ¡Nunca he “afirmado/escrito” que la Dra. Rocchietti desconoce la iconografía del formativo o del período intermedio temprano!

He escrito en dos frases (en 2014):

Most likely she was not aware of the Formative Period imagery on Boulder LUC-008 and on the Piedra la Paloma. Also the probably Early Intermediate Period imagery on many of the others stones in the Simbal area was unknown to her.

La traducción correcta de estas dos frases es (otra vez agradezco a Castillo para compartir una traducción en Español con los lectores de Rupestreweb):

Muy probablemente ella desconocía la iconografía del Periodo Formativo en el soporte LUC-008 y en la Piedra de la Paloma. También la probable iconografía del Período Intermedio Temprano en muchas de las otras piedras en el área de Simbal eran desconocidas para ella.

¡Que gran diferencia!

Cualquier lector imparcial debe admitir que la Dra. Rocchietti en su trabajo, sólo describe una pequeña parte de los grabados de Lúcumar y no demuestra haber visto los grabados formativos en ese sitio. Por lo tanto, sus conclusiones se basan en una investigación incompleta. Por esta razón las últimas palabras en la réplica de Castillo son irrelevantes: No importan los méritos (muy apreciado para mi) de la Dra. Rocchietti en el Perú o Argentina (y de Lic. Castillo) en el réplica de Castillo. Por lo tanto, la palabra “herejía”, usado por Castillo, y todo su comentario es demasiado aguda, incorrecta y no colegiada.

EN RUPESTREWEB BUSCAMOS DISCUTIR LAS IDEAS, NO JUZGAR A LAS PERSONAS (Fuente: https://espanol.groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/rupestreweb/conversations/messages/13827).

Gracias por la atención.

Cordialmente,

Maarten van Hoek

Post scriptum:

Because of the unjust criticism (link) by archaeologist Daniel Castillo Benites on this paper, I decided - in 2015 - to produce a short video about the petroglyph sites near Simbal, focussing on two sites in the valley of the Sinsicap river: Lúcumar and Cerro Prieto.

This YouTube video is an addition to my replica (link) to Castillo Benites who never had the courtesy to reply to my replica. Therefore I invite archaeologist Daniel Castillo Benites to objectively and scientifically comment on my replica and on this video as well and submit his comments to Rupestreweb Messages.